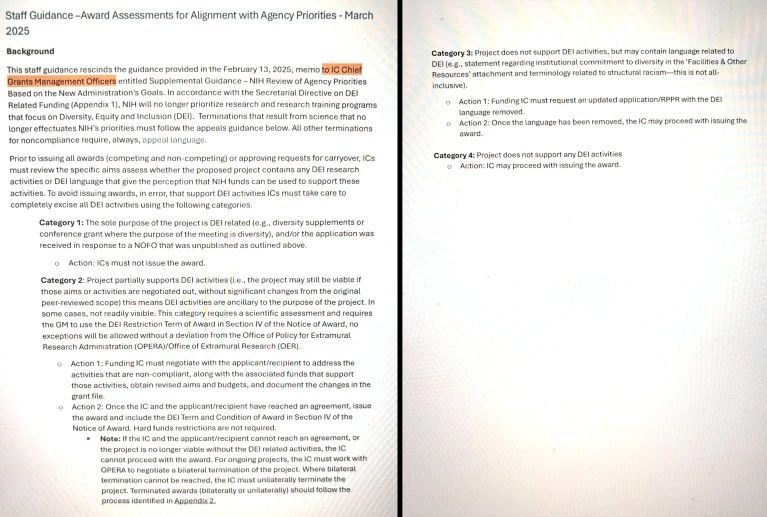

The trump administration seems to think America has a birth rate that is too low. Basically, the idea is that in this country you just can’t have enough babies born to White middle and upper middle income married couples. Proposed pronatalist measures for increasing the birth rate, many of which are likely to be championed by the trump administration, stand out for their foolishness, ineptitude, and ignorance of human behavior. As a genetic counselor, they are particularly egregious to me because of their origins of in early 20th century eugenics. Not in a vague and general way. No, you can pretty much draw a straight line between now and then, even if trump et al. might deny such a connection. Which, perhaps, they may not.

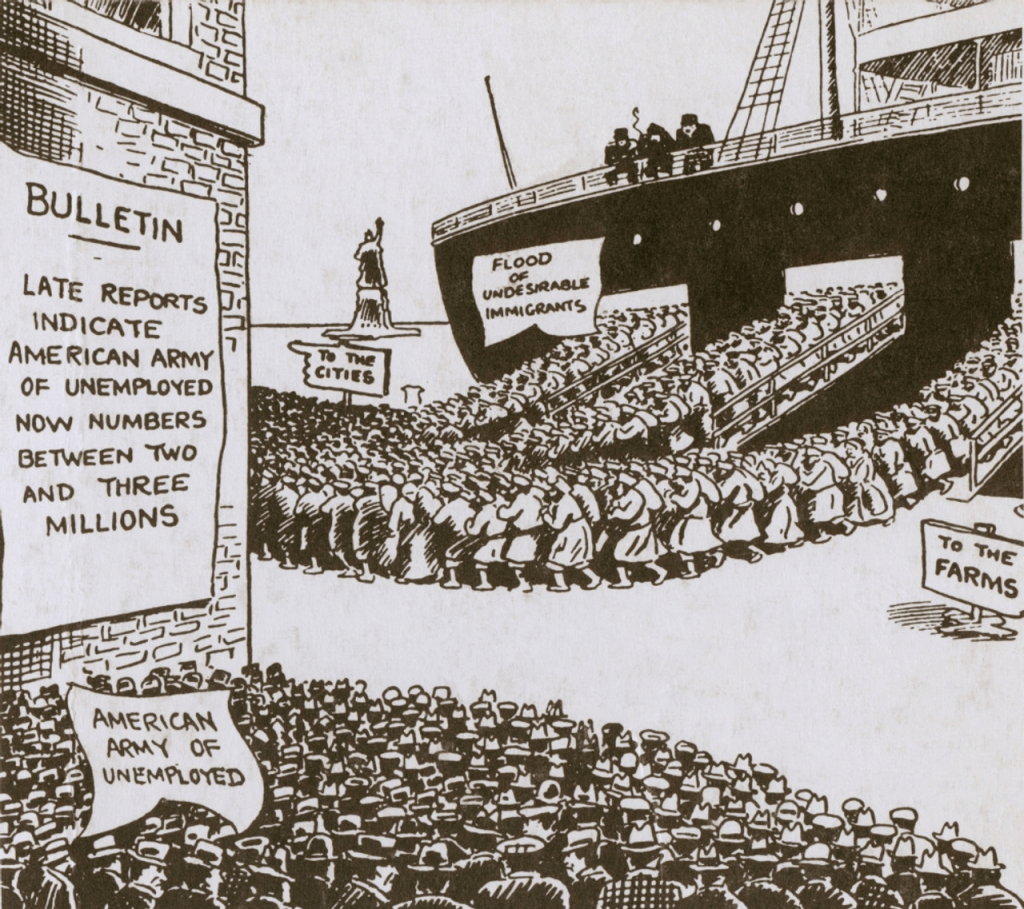

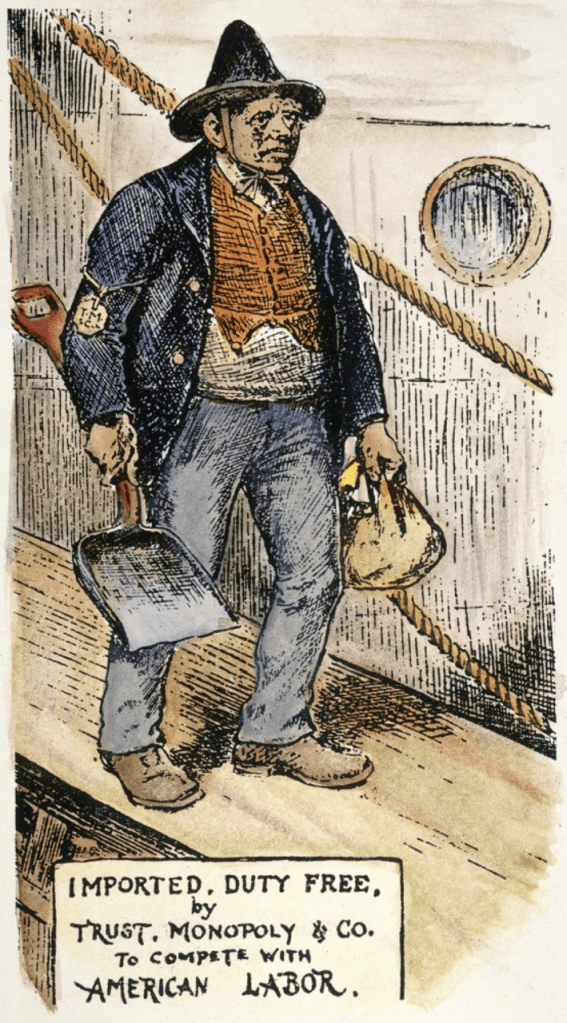

Many of polices being considered are straight out of the pages of classic eugenic texts; the only difference is the font. Limiting immigration from “undesirable” countries. Portraying immigrants as criminals, social and economic parasites, and taking away jobs from Americans. A National Medal of Motherhood for mothers with 6 or more children echoes the Nazi’s Ehrenkreuz der Deutschen Mutter (Cross of Honor of the German Mother) for mothers of 4, 6, or 8 children (corresponding to bronze, silver, and gold medals). Far-fetched to link trump policies to Nazis you say? Well, j.d. vance and marco rubio have expressed strong support for the German far right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) political party. Motherhood medals have also been promoted by Jospeh Stalin and Vladimir Putin. You would be keeping good company there, mr. president.

(Ehrenkreuz der Deutschen Mutter) Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cross_of_Honour_of_the_German_Mother

Financial and social incentives to induce families to have more children are another set of supposedly fertility-increasing policies with eugenic origins. Baby bonuses, prioritizing transit funding for areas with higher birth rates, tax breaks for families with more children, increased parental leave, and greater financial support for child care may all seem on the surface to be compassionate and supportive of parents and could be endorsed regardless of political ideology. Some version of these policies were also floated by eugenic proponents in the first half of the 20th century.

But underlying these economic policies is a deep sense of White Fear of being replaced by Undesirables. trump defines a family as married heterosexual parents. In 2022, ~ 70% of births occurred outside of marriage among Blacks, 68% among Native Americans, ~53% among Hispanics, ~52% among Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, and ~27% among Whites (most commonly among lower income White women). These policies would also de facto exclude single parents and LGBQT+ people. This ticks all the boxes on the list of people deemed genetically inferior by eugenicists. Effectively the policies would primarily benefit middle and upper middle income White parents in heterosexual marriages, with a preference for the wife staying at home to raise the children (Not too many husbands would be expected to stay at home to raise all those children; that’s the wife’s job.). Charles Davenport and Harry Laughlin, respectively the director and superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office, would give their blessings to these policies.

A historic precedent that illustrates the contradictions and biases inherent in these economic incentives are found in the history of minimum wage laws. What, you say? Minimum wage laws? What do they have to do with eugenics? And even if these laws have their faults, aren’t they better than no laws at all? Here I base my discussion primarily on a book and an article by the economist T.C. Leonard.

To be clear, non-eugenic factors were involved in establishing minimum wages. But eugenically-minded economists played a critical role in establishing these policies and putting them into practice. Many of America’s leading economists in early 20th century were also strong advocates of eugenics. Edward Ross, an economist at Stanford University* and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was a proponent of the Race Suicide Theory and strongly opposed immigration, especially from Asia. Harvard economist Irving Fisher** served as president of the Eugenics Research Association, helped found the Race Betterment Foundation, and was on the advisory board of the Eugenics Record Office. Simon Patten, an economist at the Wharton School*** who served as President of the American Economic Association, supported eugenics and “eradication of the vicious and inefficient.”

For these economists, eugenics was seen as a way to economically support the (White Anglo-Saxon) American worker. They felt that American workers’ jobs and family sizes were threatened by low wages. If workers couldn’t make enough money, they would not be able to support large White families. In the economists’ view, the source of low wages was competition from people who were willing to work for the lowest wages possible (I guess no one thought it conceivable that employers would voluntarily pay workers a decent wage).

Who were these people threatening the American work force and family? Immigrants were one group, primarily people not of Anglo-Saxon ancestry, in much the same way that trump has argued that “illegal immigrants” steal jobs from Americans. These anti-immigrant advocates despised all non-Anglo-saxon races more or less equally, at a time when race was defined differently and included the Italian Race, the Slavic Race, the Chinese Race, the Irish Race, etc. William Z. Ripley, professor of economics at MIT and Columbia University, was the author of The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study, a book that argued that race explained human behavioral and psychological traits, partly the result of heredity and partly the result of cultural upbringing. It was felt that these undesirable immigrants were “racially predisposed” to accepting low wages and living in sub-standard conditions.

But it was not only immigrants that worried the economists. They also fretted about women (who were supposed to stay at home and raise families rather than compete for jobs), children (these economists tended to support mandatory childhood education and child labor laws because these laws kept kids off the job market and competing with adults), the “shiftless”, the poor, African-Americans, and the “feeble-minded.” If low paying jobs paid at least a living wage supposedly guaranteed by minimum wage laws, then White Anglo-Saxon workers would be willing to accept these jobs and go on to have large families. And if lower paying jobs were filled by White workers, then the “undesirables” would be unemployed and less likely to have larger families or to even migrate to America at all. Voila! America would be saved!! Or so the reasoning went. Spoiler alert: it didn’t really work, despite legislative success. By 1923, 15 states and the District of Columbia had passed minimum wage laws. The federal Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established a minimum wage of 25 cents an hour.

How one defines a liberal, a conservative, a progressive, a eugenicist, or a critic of eugenics changes over the course of history. Many of these economists were considered Progressives and liberals but none of them would remind you of Paul Krugman, Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or Elizabeth Warren. Minimum wage laws, while still controversial but for different reasons, no longer carry eugenic connotations. A number of prominent geneticists who were strong critics of eugenics, such as Ronald Fisher, Herman Muller, and Lancelot Hogben, also strongly supported policies that today we would label eugenic because they called for policies to encourage reproduction among “the most fit.”

Eugenic ideology never really died, even if no society ever died off because of over-breeding by the genetically unfit. Like a zombie, it keeps coming back to haunt us in different forms, separating the world into the genetically superior and the undeserving genetically inferior. Sometimes eugenics comes under the guise of maleficence with intent to harm and sometimes under the guise of beneficence with intent to help society. But whatever its form, it never does any good.

____________________________________________________

*- Stanford had an intimate history with eugenics from its founding. Besides Ross, Leland Stanford, Jr., Stanford’s founder, and David Starr Jordan, Stanford’s first president, along with several faculty members up through the 1960s, were ardent eugenics advocates.

** – In a weird historical echo of eugenics and phony-baloney medical beliefs that evoke Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Fisher’s daughter was treated for schizophrenia by the psychiatrist Henry Cotton, who believed that the cause of schizophrenia was bacterially infected tissue in bodily recesses. Cotton “treated” schizophrenia through various surgical procedures including dental extraction, colectomy, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, cholesytecomy, gastrectomy, and orchiectomy. Fisher’s daughter underwent a partial bowel resection and died of complications from the surgery, one of Cotton’s many unfortunate victims. RFK, Jr., may not exactly be a eugenicist, but his attitudes toward autistic people sure smacks of it. Please, no one let RFK, Jr., know about Cotton’s ideas.

***- In another historical irony, trump earned an economics degree from the Wharton School in 1968.