by Ambreen Khan, Kim Zayhowski, Robert Resta, and Laura Hercher

This piece is our team’s account of censorship and threats from members of the genetic counseling community. It is both testimony and a demand that our profession do better. We were twice scheduled to present a webinar on the threat of modern eugenics – only for both events to be canceled after anonymous complaints and undisclosed claims about threats and safety. When organizations shield reputation over transparency, they marginalize dissent and chill scholarship that is essential to our clinical and ethical responsibilities. Institutional silence is not neutrality.

What actually happened?

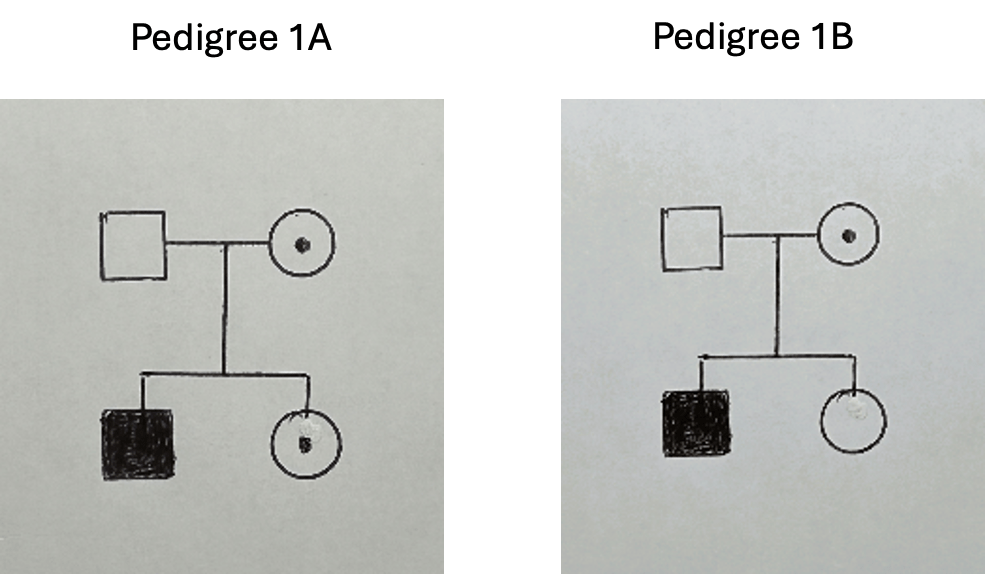

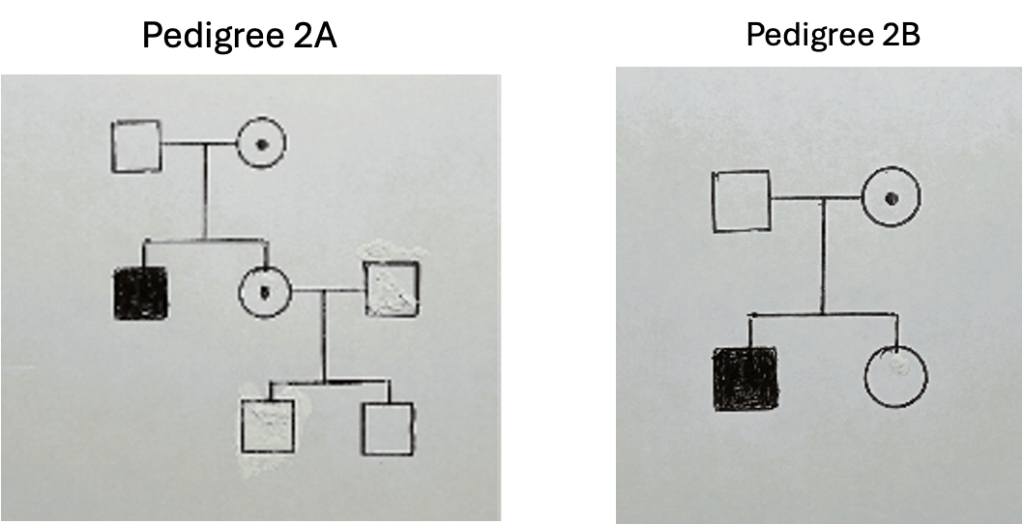

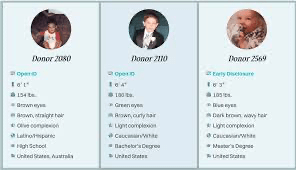

Our webinar’s purpose was simple and urgent: to connect the historical roots of eugenics to the present. Genetic counseling partly emerged as a response to twentieth‑century eugenic abuses rooted in Francis Galton’s nineteenth‑century theories. We aimed to show that these ideologies are not relics but active influences – visible in the United States president’s eugenics-coded rhetoric, in technocratic visions of positive eugenics, and in colonialism and imperialism across the globe. We planned to demonstrate how sloppy science, genetic determinism, dehumanization, and essentialist language flatten human complexity and create openings for misuse; to interrogate whether elements of contemporary genetic counseling echo eugenic logic; and to engage participants in concrete strategies for explicitly anti‑eugenic practice.

Timeline of cancellation #1:

- January 31, 2025: The proposal was submitted for the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) Annual Conference for a presentation on modern eugenics.

- March 28, 2025: NSGC asked that the proposal be recast as a “Community Conversation” – a recorded webinar with a facilitated live discussion intended to extend reach.

- June 4, 2025: We returned the revised proposal to NSGC. The final speaker team was Robert Resta, Laura Hercher, Ambreen Khan, and Kim Zayhowski. The live discussion was scheduled for September 29, 2025.

- Summer 2025: We had many meetings as a presenter team about the content of each of our presentations. We assembled volunteer moderators, developed the session as a dialogic educational space, and stayed in regular contact with NSGC liaisons, sharing the slide deck and session plan for review.

- September 4, 2025: The final recordings were submitted to NSGC, which were then posted for NSGC membership. We were informed several hundred people signed up for the event.

- September 16, 2025: NSGC removed Ambreen Khan’s segment (“Reconsidering Eugenics through a Global Lens”) from the posted materials pending “fact‑checking” after complaints about alleged inaccuracies.

- September 22, 2025: Following NSGC’s “fact-check,” the segment was restored with an appended reference list, and an overall disclaimer NSGC required stating that views expressed were the presenters’ own.

- September 25, 2025: Four days before the scheduled live conversation, NSGC canceled the webinar and removed the recording. NSGC emailed the presenters and attendees, and referenced threats of violence to leadership and the organization as the cause of the cancellation. They provided presenters with no details, documentation, or evidence of those threats. Both emails said that the topic of eugenics would be addressed at a later date. NSGC paid presenters their honoraria.

- October 6, 2025: One presenter followed up via email to request specific information regarding the nature of the threats, whether their source had been identified, what content provoked them, and if law enforcement had been involved. The presenter emphasized that, as a speaker for the upcoming annual conference, understanding any security risks related to the presentation’s content was essential for safely preparing future talks.

- October 8, 2025: NSGC acknowledged that the questions were “very reasonable” and stated that the source of the threat had been identified and “addressed” with legal counsel, leaving “no ongoing concern.” They offered no specifics on the threats’ content, their origin, how they were handled, or what material had provoked them. Without these details, the presenter team could not evaluate their own safety for future engagements. To date, the talk has not been rescheduled and no explanation has been provided for why restoring the recording is not possible if the threat has been fully resolved.

Timeline of cancellation #2:

- December 16, 2025: A genetic counseling graduate program’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice Committee reached out to the presenter team and invited a similar presentation on modern eugenics for a webinar open to genetic counselors and students. The event was organized by students and approved by program leadership for February 9, 2026.

- January 28, 2026: The program emailed the presenter team and canceled the webinar, citing concerns about “belonging for all” and “potential lack of balanced perspectives” that they claimed would violate the university’s nondiscrimination policy, along with anticipated safety concerns. The email stated that the messages sent to the University expressing concerns had assumed the event’s material was the same as the Community Conversation referenced above. The program confirmed the content had not been fully reviewed before making the determination to cancel. One presenter noted that the cited university policy explicitly protects academic free speech even when it may provoke opposition or external pressure directed at the faculty or the institution. Promotional social posts (which had attracted 100+ likes and supportive comments) were deleted without announcing the cancellation.

Targeting and double standards

During NSGC’s “fact-checking” process, one speaker, Ambreen, was singled out for the portion of her presentation which analyzed genocides in the United States, Germany, Rwanda, and Gaza through the lens of medical ethics and eugenics. Complaints about her presentation were framed as questions of academic veracity. NSGC restored her content after review with appended references. In our view, this outcome indicates that the complaints were motivated less by demonstrable concerns about factual integrity and more by ideological opposition to her inclusion of Gaza and her critique of Israeli policies.

Ambreen and the Council on American–Islamic Relations (CAIR) sent NSGC a formal letter on November 10, 2025, urging procedural reforms. CAIR offered to help NSGC “review internal procedures for handling complaints to ensure that concerns about content do not serve as a pretext for suppressing marginalized voices or politically sensitive topics.” To date, more than three months later, neither Ambreen nor CAIR has received any acknowledgement or follow-up.

The CAIR letter underscored the harm of institutional repression, stating:

“One of the so-called citation concerns involved Ms. Khan failing to include a reference to Israel’s offer to treat Gazans in Israeli hospitals. It appears that Ms. Khan’s detractors simply disagree with her assertion that what Israel has done in Gaza is tantamount to genocide, which is a position they are able to hold and argue, but it should not result in the systematic silencing, censorship, and reputational harm to Ms. Khan. To be clear, Ms. Khan’s citations appear to be adequate; the disagreement appears to rest not on the veracity of her sources but on interpretation and analysis, which is within the scholarly discretion of any presenter. Singling out her presentation for heightened scrutiny and censorship has created a hostile and chilling environment for scientific and ethical dialogue. … Unfortunately, this is not the first time NSGC has censored members regarding the genocide in Gaza. We view this as an opportunity to engage in reasonable and appropriate restorative steps.”

What is at stake?

Censorship is not new to genetic counseling: our profession has navigated pressure over which histories, patient stories, and ethical critiques are acceptable to teach and debate. In recent years that pressure has intensified, playing out both publicly – high‑profile cancellations, wide-spread written petitions, and calls for professional sanctions – and privately, as quieter demands to remove material from syllabi, discourage certain research topics, or advise speakers to avoid specific language.

When educators and researchers preemptively “tone down” lectures, avoid case studies, or divert research away from challenging topics out of fear, they inflict a lasting corrosion of knowledge. Self‑censorship is the stealth weapon: curricula thin, research agendas narrow, and trainees learn that caution equals professionalism. Unlike an explicit ban, self‑censorship is invisible – until whole domains of knowledge vanish from professional discourse. That quiet retreat institutionalizes ignorance.

When a government or institution decides which ideas are acceptable, it ceases to be a sanctuary for inquiry and becomes a tool for social control. Across the world we see a coordinated strategy to suppress scholarship: in Hungary, the government outlawed gender studies to replace independent scholarship with state-sanctioned curricula; in India, the state uses police, laws, and bureaucracy to silence critics; in the United States, topics like Palestinian rights and Critical Race Theory are suppressed through legislation and institutional pressure.

This is not about ideological grandstanding; it is about clinical competence. Clinicians who cannot name the political and historical dimensions of eugenics are ill-equipped to safeguard patients from coercive programs or discriminatory allocation of care. Patients most at risk – disabled people, people seeking reproductive care, BIPOC communities, immigrants – pay the price. If our institutions silence education on the role of eugenic impulses in shaping border policy, how can genetic counselors recognize its modern iterations targeting immigrant patients? And if we cannot name Gaza or Sudan as sites where medical ethics are violated, what framework do we have to recognize – much less resist – the same violations anywhere else?

Teaching should be emancipatory, not neutral. Thinkers from Paulo Freire to bell hooks and Henry Giroux frame teaching as naming injustice and treating the classroom as a site of ethical resistance. The Palestinian ideal of Sumud (صمود) – a steadfast, rooted perseverance against erasure – extends this vision: learning itself becomes a daily act of standing against oppression.

Yet educational institutions too often prioritize procedural risk management over ethical clarity. When institutions invoke “safety” without sharing assessments or supporting speakers, the loudest and most aggressive opponents effectively decide what may be taught.

Eugenics thrives not only on coercive policy but on silence – on what is not taught, not researched, and not challenged. When institutions bow to intimidation and erase critical inquiry, they remove guardrails that might otherwise prevent discriminatory policies and coercive practices.

A call to action

We as a genetic counseling community must decide whether genetic counseling will be a profession that names power, confronts history, and defends the scholarship our patients depend on, or one that retreats into procedural silence when challenged. That choice belongs to all of us. The genetic counseling community does not have to, and should not, agree about everything but we should be able to respectfully, thoughtfully, and safely engage in debate and discussion.

Our team asks academic programs and professional societies to adopt the following policies to protect both safety and academic integrity:

- Publish transparent moderation policies and threat-protocols

- Make public criteria for removing or modifying recorded or live content, including what level of threat justifies cancellation and what evidence is required.

- When “safety” is cited, share a summary of the threat assessment with presenters and with the membership (while protecting any legitimately confidential investigative details).

- Include presenters in safety planning

- Share threat assessments and possible mitigation strategies with speakers.

- Collaborate on concrete steps (e.g., moderated Q&A, delayed posting, platform security, legal support) before deciding to cancel.

- Provide visible, material support to targeted scholars

- Offer logistical, legal, and public backing (e.g., an institutional statement affirming vetted content, assistance with security measures, and a designated liaison for harassment complaints).

- Establish clear anti-retaliation policies for educators, students, and members who report censorship or advocate for reinstating removed content.

- Create an independent appeals and review mechanism

- Establish a review process for decisions to remove content or cancel events, with a timetable for review and public reporting of outcomes.

- Commit to essential curricula

- Ensure core training includes the political and historical forces shaping medical care in general and genetic counseling specifically, and defend those curricular commitments from suppression.

- Remedy past harms

- Publicly acknowledge cancellations that lacked transparency, reinstate or re-record content where appropriate, and issue formal apologies and restorative steps for presenters who suffered reputational harm.

Credible threats of violence are serious matters that deserve careful attention and response. Our demand is procedural: when safety is invoked, institutions must show evidence of due process, involve presenters in mitigation, and exhaust alternatives to cancellation before erasing vetted educational content.

In an era when threats are weaponized to control knowledge, yielding to intimidation forfeits our capacity to confront hard truths about power, policy, and medicine. Our duty is twofold: protect people from immediate danger and protect the integrity of knowledge itself. Silence may be easier, but it is a dangerous abdication. We are all responsible for the profession we build. Defend evidence. Defend teaching. Defend the people – patients, students, clinicians, and scholars – who depend on both.

Author note: This account is based on our direct involvement as presenters and on preserved documentation and correspondence with the institutions referenced. It reflects factual information available to us through our participation and our professional judgment. We remain available to address and correct any substantiated factual inaccuracies. The opinions and interpretations herein are exclusively our own and do not necessarily reflect the positions of our employers or affiliated institutions.