“All human beings are commingled out of good and evil.” Robert Louis Stevenson, author of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr.Hyde

Genetic counselors are good people who want to do good. And that also goes for the vast majority of clinicians in all specialties and support staff who I have ever worked with. We may have brief dalliances with cynicism but overall we strive to be highly competent professionals who deliver compassionate care to patients in hopes of improving their physical and emotional health in small and large ways. We subscribe to the ethos of Do-Goodism – we strive to do good because it is the right thing to do. It’s why we drag ourselves out of bed and show up for work every day. It sure isn’t out of love for the daily commute, an overloaded work schedule, or the out-of-touch-with-reality dictates of upper level management.

Do-Goodism is a, well, good thing. There should be lots more of it in the world (especially among governments). But Do-Goodism has its downsides. Okay, let me stop right there. I am not criticizing Do-Goodism nor am I advocating for D0-Badism. So don’t accuse me of criticizing people for being good. But a problem inherent to Do-Goodism is that can make it very difficult for us to see and acknowledge that when we try to do good things there can be bad outcomes. Our Good Filters block out the Bad Rays generated by our well-meaning actions. Recall what the road to you-know-where is paved with.

A good historical example of the blinders of Do-Goodism is eugenics, that bogeyman of every historical narrative of genetics. While nowadays we look down on eugenics with moral scorn, in fact, with a few obvious exceptions, many eugenics advocates in the US, the UK, and elsewhere genuinely thought they were improving not only the greater good of society but also the “dysgenic” families themselves. Philosophically, eugenics may have been closer to “a kind of genetic social work” than Sheldon Reed would have been comfortable acknowledging. Another historical example are the 19th century alienists who ran the so-called madhouses – whose records were critical to the development of modern genetics and eugenics – where “lunatics” were housed and supposedly cured with fantastical rates of supposed psychiatric problems such as masturbation and menstrual disorders.

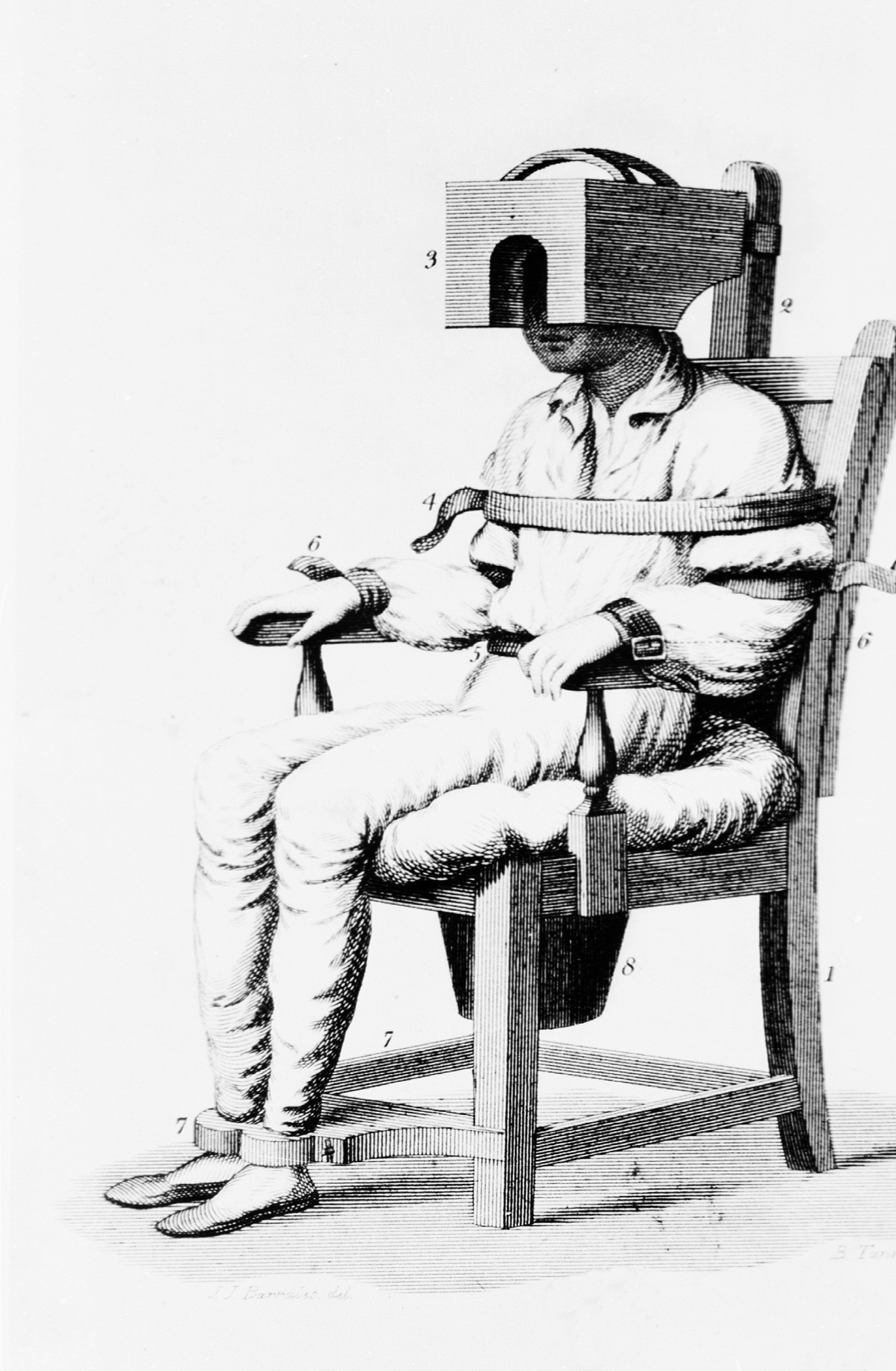

Br. Benjamin Rush’s Tranquilizer for treating patients with mental illness. It “binds and confines every part of the body … Its effects have been truly delightful to me. It acts as a sedative to the tongue and temper as well as to the blood vessels.”

Do-Goodism still pervades genetic practice today, albeit in different forms. We sometimes advances policies, practices, and tests in the name of “helping people” when the benefit/downside ratio has not been well established. In my own practice of cancer genetic counseling, I think of how seamlessly BRCA testing has expanded to gene panels that include dozens of genes, many of which are of uncertain clinical utility. Even after ~25 years of research on BRCA we still debate the lifetime cancer risks, the mortality reduction of risk-reducing mastectomy, and the benefits of endocrine prophylaxis. In the US, Lynch syndrome patients are encouraged to join The Annual Colonoscopy for Life Club but the data is still not settled as to whether an annual colonoscopy is more beneficial than less frequent exams . And these are the genes that we know fairly well. The clinical implications and best risk-reducing strategies for carriers of other typically tested genes like NBN, RAD51D, or BARD1 are pretty much anyone’s educated guess.

There are complex reasons why gene panel testing has become so widely incorporated into medical care. but I am pretty sure one of the motivating reasons we offer panel testing is that we think that by “finding an answer” to explain the family history, we are benefiting our patients. But are we really helping these patients by offering breast MRI screening with its high cost and false positive findings, risk-reducing surgeries, etc.? Are we explaining their family histories with these tests? Maybe we are, maybe we aren’t. We should have had that answer in hand before the testing was incorporated into clinical practice instead of turning a bunch of clinical patients into an unplanned and haphazard research project.

This was brought into sharp focus for me with a BRCA positive kindred I have been working with. A family member was identified as an asymptomatic BRCA mutation carrier, subsequently underwent risk-reducing surgery, and an occult Fallopian tube cancer was identified at an early enough stage that cure was highly likely. This made me feel like I should notch a victory mark on my belt. After all, preventing ovarian cancer is understandably offered as one of the urgent justifications of BRCA testing. I felt that I pulled the rug out from under ovarian cancer’s evil legs – until the patient died of complications of MRSA acquired during her hospital stay. And this in a situation where everyone would agree that the data strongly supports surgical risk-reduction. Should we be risking such outcomes by offering testing for genes in which there is no large body of research to support clinical recommendations?

Do-Goodism also pervades other areas of genetic testing and counseling. Expanded carrier screening. Noninvasive Prenatal Testing. Advocating for whole exome sequencing of newborns or of healthy adults. Direct-to-Consumer genetic testing. Clinicians and labs offer these tests in the name of helping people and democratizing genetic testing, but this can lead us to psychologically manipulate ourselves into ignoring or downplaying studies that suggest that maybe we should step back before we aggressively offer these tests. The blinders of Do-Goodism can be further exacerbated when our jobs seem to compel us to offer bigger and supposedly better tests to keep up patient volumes or corporate profits. Do-Goodism is not confined to genetics, of course. It also underlies long-standing debates about routine mammography, PSA screening for prostate cancer, and cardiac defibrillators in medically fragile elderly patients, to name a few.

We are not bad clinicians or evil profiteers, just human beings struggling with our psychological limitations. It’s why we need to thoughtfully listen to thoughtful critics who question our clinical practices. They make some very good points but only if we can allow ourselves to see them.

This is a much needed discussion in all of medicine. A major concern I have when making recommendations to patients is will it really be helping them? I recently read a book called The ‘end of medical reversals’ and it argues that much of what is practiced as evidence based medicine has in fact not been proven effective or is later shown to be harmful. I think this book is a must read for all medical professionals committed to providing the best care possible.

Thanks for the tip about the book. Looks like it is called “Ending Medical Reversals: Improving Outcomes, Saving Lives”. Will definitely try to check it out.

Thank you for so thoughtfully raising this issue. I’ve been pondering this so much in my work with patients with hypermobility EDS and other conditions that “cause” pain. I’ve taken an interest in the neuroscience and psychology of pain, and I have learned how beliefs and behaviors often contribute more to chronic pain than any underlying structural problem. I can’t help but wonder if we are really doing these patients a disservice in genetics when we tell them a genetic diagnosis explains their pain, they will continue to have pain, and it has nothing to do with their psychology. Patients seem so relieved and grateful when we tell them they have a diagnosis and it isn’t “all in their heads” – and that feels good as a provider. But pain research shows that the nervous system, unconscious brain and “mind-body” factors are involved in all chronic pain, regardless of the initial trigger. No, it isn’t “all in their heads”: they aren’t imagining the symptoms or pretending. But pain is in the brain, and there are techniques to help people re-train the nervous system to reduce and even eliminate pain. As a gc, I’ve never been trained in how to discuss those things with patients. Could the way we communicate about this disorder create a self-fulfilling prophecy? And are we giving people an excuse to become dependent on disability benefits and pain medications. When we tell them to avoid certain things that might cause more pain, are we asking them to withdraw from the rewarding parts of their life that can actually improve pain? This fear was reinforced when I read these NY Times articles about how belief influences physiology more than 23andMe-style genetic risk factors, and about how genes and the provider-patient relationship actually influence the placebo effect. Check them out, they made my jaw drop:

and

Suzanna- Interesting, I read that article today and my thought was —this is why genetic counseling can be so helpful – because not just what information we present but how we present it and how a patient feels about it is as important as the information itself. My reference points are prenatal and cancer rather than EDS and neuro or pain-related disorders though.

I’m also slow to comment on this article but really appreciate these points being brought up. The push is toward more more more more testing. It’s easier to just do-the-test and to just do more rather than less testing. Not unlike how it’s easier for a pediatrician to just prescribe antibiotics instead of discussing with a parent something is probably viral or just listening to how and why they are worried about their child.

And overall I usually find myself in the camp of more testing, but there are too many perverse incentives at play to have as much discussion around this as we should be having. I don’t see this changing as long as there is not adequate reimbursement for genetic counselor time.

Pingback: The American Plan: The Incarceration and Forced Treatment of “Good Time Girls” | The DNA Exchange