There are many reasons people undergo DNA analysis. Medical decision making and risk assessment. Prenatal screening and diagnosis. Ancestry testing. Wellness and lifestyle advice so someone can reap profits off of largely useless data. Parentage testing. Police investigations. The analysis might involve different tests, such as sequencing your entire genome (give or take a few million base pairs), targeted portions of it, single gene sequencing, single nucleotide polymorphisms, or karyotyping, to name a few. The results are usually treated as a static bit of information that is an accurate representation of your genetic make-up throughout your lifetime. The implicit message often is that you are the external manifestation of this single DNA test, like a DNA sequence was a map with an arrow pointing at it with the message “You are here.”

But really, no test can come close to capturing all of the DNA in your body. Any one test or set of tests , while they may be highly accurate in the right hands, only capture a DNA sequence in a particular tissue(s) at a particular moment in the lifespan and is useful only for a specific reason such as cancer treatment, assessing disease risk, or reproductive decision making. It’s a snapshot taken with a single narrow lens for a single purpose, not an ongoing video using a multidimensional wide-angle lens. The snapshot could look quite different depending on which tissue is sampled or if the snapshot is taken at a different moment in time.

Let’s start at The Beginning, or actually, just before The Beginning. As the result of meiotic scrambling, maternal and paternal chromosomes will be distributed among the gametes in a bewildering mix of maternal and paternal contributions. Like about 8 million possible different combinations of maternal and paternal chromosomes. Estimates vary because who analyzes each oocyte in the fetal ovaries, but a 20-week female fetus probably has somewhere between two to eight million oocytes. In other words, it is possible that each of those oocytes has a unique combination of maternal and paternal chromosomes. The number of aneuploid oocytes in utero is unknown, but during reproductive years around 10% of oocytes are aneuploid or have an unbalanced structural aberration, with the percentage increasing with maternal age. Trinucleotide expansion repeats responsible for Fragile X syndrome and Huntington disease can arise in oocytes during meiotic prometaphase 1.

In a young male’s typical ejaculate, with tens to hundreds of millions of sperm, there is a higher but still low probability that maybe a few of those sperm will have identical maternal and paternal chromosomal contributions. But about 10-15% of sperm cells have chromosomal abnormalities, with perhaps 90% of those being structural rather than numerical. On top of this, de novo pathogenic gene variants can arise in any gamete, with the probability increasing with a paternal age. And no one has any idea of the frequency of de novo variants in non-coding regions in spermatozoa or oocytes.

Perhaps the only time in human development that we have a single genome is immediately at conception, although that may apply only to nuclear DNA since the mitochondria of the fertilized egg could be heteroplasmic. But as the fertilized embryo undergoes mitosis, different genomes arise almost immediately. Chromosomal mosaicism is detected in a significant number of embryos; anywhere between 2 and 40%, depending on a number of factors. About 2% of CVS specimens, which are derived from the fetal aspect of the placenta, are chromosomal mosaics. Mosaic single gene variants can also arise in neuronal progenitor cells, primordial germ cells, and other tissues. Fetal cells and cell free DNA work their way into in maternal circulation during pregnancy and the cells can persist in maternal circulation for years, a form of microchimerism.

Beyond conception and the embryonic period, somatic gene mutations regulary arise in fetuses, children, and adults in many different tissues. Some mutations are repaired, some persist and are clinically insignificant, and others make significant contributions to human disease. Cancer, for all intents and purposes, arises from somatic mutations. Cancer cells themselves then often go on to develop a bewildering array of mutations as the cancer grows and metastasizes. Mutation profiles can vary within the same affected tissue or between affected tissues. Further DNA damage can be induced by chemotherapeutic agents. Then there’s chromothripsis, where the genetic wheels come off altogether.

Beyond cancer, other medical conditions can arise from genomic variability. Trinucleotide repeats can expand and contract over time and can vary between and within tissues and may significantly contribute to adult and childhood onset neurological disease. Mosaic or segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by post-zygotic NF1 mutations.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is the result of somatic mutations in hematopoietic tissue and occurs in about 10% of people age 70 or older. CHIP is associated with an increased risk of many diseases, such as hematologic cancers, coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, and pulmonary disease.

X chromosome inactivation and mosaicism are another source of intra-person genetic variability. One X chromosome will be largely inactivated in anyone who was born with more than one X chromosome. This could have significant clinical effects, such as manifesting symptoms of Duchenne muscular dystrophy or hemophilia, often depending upon which X chromosome is inactivated and in which tissue. Furthermore, people with more than one X chromosome tend to lose one of their X chromosomes in some of their cells, especially as they age, such that they are X chromosome mosaics, which might lead to cognitive impairment.

Transposable elements (transposons and retrotransposons) are DNA remnants of microbial organisms from our evolutionary past that have been integrated throughout the human genome, the evolutionary equivalent of internet cookies. Perhaps as much as 50% of the human genome is composed of transposable elements. These bits of microbial DNA regularly rearrange themselves within our genomes (thank you Barbara McClintock) during evolution and also within our bodies during our lives, rejiggering DNA sequences and contributing to the development of human diseases such as cancer, hemoglobinopathies, and neurological disorders.

The DNA of immune cells constantly alter themselves through processes such as somatic recombination and somatic hypermutation. This variability allows the immune system to respond in highly specific ways to so many different types of infection and cancers, and to help the healing process.

On top of all of this, we co-inhabit our bodies with all sorts of bacteria, viruses, protozoa, archaea and God knows what else, the composition of which changes regularly. In fact, most of the cells, and therefore most of the DNA in our body, are microbial (it varies at any given moment in time, like after a bowel movement). Since these microbes are symbiotic living parts of our bodies, their DNA is also our DNA.

Mitochondria are likely the remains of a microorganism that was integrated into host cells in our deep eukaryotic past. Mitochondrial DNA can be heteroplasmic, that is, any given mitochondrion can acquire a wide range of mutations that do not occur in other mitochondria. Heteroplasmy can be a significant source of medical conditions, depending on the degree of heteroplasmy and its distribution.

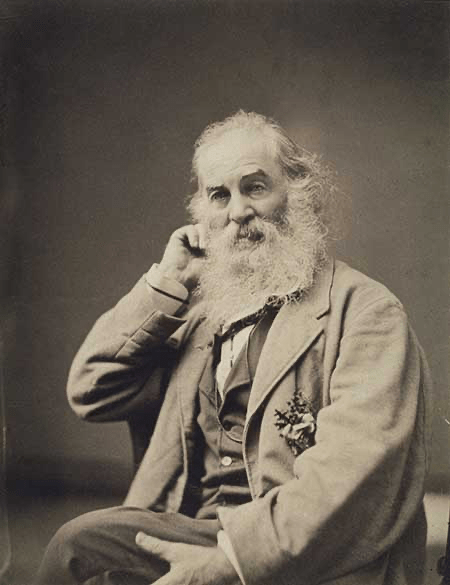

Intra-person genetic variability is one of the many reasons it is foolish and inaccurate to say that our DNA defines us. Each of us has many constantly shifting DNA sequences throughout our bodies and each sequence can play out in our lives in different ways at different times. The interaction of these sequences with each other and with our cellular, bodily, and external environments is so exquisitely and frustratingly complex that it is beyond comprehension by human or, I will wager, artificial intelligence (how could AI analyze the entirety of a person’s DNA sequences if it is impossible to capture all of those sequences at once, on top of which those sequences change over time?). Human beings are infinitely more complex than the near infinite sum of each of our body’s many genomes. We should all sing the body electric.

The love of the body of man or woman balks account, the body itself balks account

– Walt Whitman, “I Sing The Body Electric”

You Are Not Here —>

———————————————————————————————–

All images, except for the image of Walt Whitman, were AI generated. All of the text was human-generated by me.