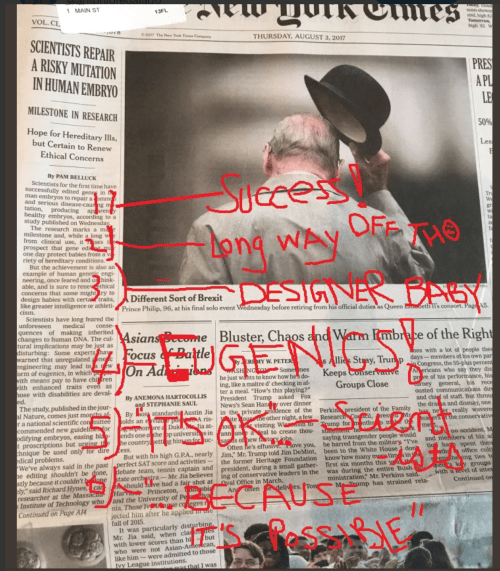

Publication this week of a paper by reproductive biologist Shoukrat Mitalipov and others put the subject of editing little baby humans front and center – above the fold news in the NY Times. Universally, the Mitalipov study was recognized as a milestone, and so it appears to be – a milestone on our journey to…wherever it is we are headed.

What did they do, and why is it important? Mitalipov improved greatly on previous efforts at germline editing, targeting embryos created using donor eggs and sperm carrying a pathogenic variant in the MYBPC3 gene associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Modification was successful over 70% percentage of the time, no off-target effects were detected, and only one of the 58 embryos was found to be a mosaic of altered and unaltered cells. While significant safety and efficacy concerns remain to be addressed, this work goes a long way toward validating the idea that, sooner rather than later, clinical use of this technology will be a realistic possibility.

The experiment raised hopes, but also some questions. CRISPR is often described as a DNA version of a search-and-replace function in a word processing program, but CRISPR itself only does search-and-remove. The ‘replace’ part leverages the cell’s own machinery for fixing breaks in DNA, and its innate penchant for tidying up any loose ends. Quick to the breach, cells can often be coaxed into using a template for the repair if one is provided along with enzymatic scissors and a guide RNA, allowing us to insert a custom DNA sequence. This bespoke DNA can be anything, but in this case it was meant to be a benign version of the MYBPC3 gene. In a surprising development, the cells preferentially ignored the synthetic template and used the unaffected version on the sister chromosome as a guide instead.

This had the desired effect of introducing a functioning wildtype gene, but if it is not overcome as a technical issue, will limit the range of what can be achieved via gene editing. This model doesn’t work at all with recessive disease, where there are two copies of the pathogenic variant. Additionally, it would not allow for the introduction of DNA sequences other than what is carried by a parental allele – a capability which is, I would argue, the truly unique feature of gene editing.

Articles about CRISPR may (and usually do) talk about its potential to prevent Mendelian diseases like Huntington’s or sickle cell, but we are already capable of preventing transmission of these diseases using IVF with PGD to identify embryos that are unaffected. Yes, as has been pointed out, this is not foolproof. A round of IVF may produce no unaffected embryos. In rare circumstances, one parent may be homozygous for an autosomal dominant disease. These are non-trivial events when they occur but they are rare and limited circumstances. For the rest, replacing one expensive and complicated technology with another is incremental progress at best, and not the reason why this story was A-1 on the NY Times website. Media interest, let no one be confused, was about the potential of CRISPR to produce what they referred to (inevitably) as designer babies.

Antonio Regalado of the MIT Tech Review decodes media coverage of human genome editing

Can the technology produce designer babies? This would be an easier question to answer if designer babies were actually a thing that you could define, but they’re not. Generally, what people mean by ‘designer baby’ is one created through any use of reproductive technology to ensure specific traits, as opposed to using identical technology to avoid diseases. The problem with this is that drawing the distinction is a bit of Impressionistic painting – clear from a distance, but blurring together when you get close. A number of articles this week suggested that designer babies can’t happen because traits are not something that can be manipulated by tweaking a gene or two (here and here). This is comforting but may not hold up. It’s fair to say that you can’t tweak general intelligence – but what about, for example, executive function? And while we’re on it, would that be increasing intelligence (bad) or avoiding ADHD and other mental health problems (good)?

But this is leading me into rabbit holes, where we debate what is or might be or could be possible, when just now I want only to say that the potential of gene editing to add an entirely new dimension to what we can currently offer is bound tightly to its ability to introduce DNA sequences that are different from what either parent can contribute. When we are able do that, we can expand the concept of what it means to ‘choose’ a child’s genotype. We can add rare variants that confer some protection or competitive edge. We can even contemplate adding synthetic variants designed in a lab and not borrowed from natural experiments. When move past embryo selection to embryo improvement, we will have our little Gucci baby whose possible existence causes so much consternation.

So does this week’s blockbuster paper put us closer to that day? Yes, because the technology has moved forward a giant step. Not that technology ever moves backwards, but the speed with which it has improved is staggering, and while momentum is not going to carry it over the remaining hurdles like a hot wheels car going loop the loop, it does make it easier to assume that all technological barriers will eventually fall. But at the same time, the template surprise reminds us that every step forward reveals another twist in the road.

Are we almost there? Who knows. If 2016 taught me anything, it was to stay out of the prediction game.

So what would a wise republic do? Coincidentally, a workgroup under the auspices of the American Society of Human Genetics published a paper yesterday in the AJHG laying out recommendations for public policy on human germline editing. The position statement was approved by ASHG, NSGC and 9 other organizations from six continents (full disclosure: I am one of the co-authors). The take home point is that modification of the human genome (egg, sperm or embryo) would be premature at this time but may be justified in the future, providing that there is a compelling medical rationale, an evidence base to support its use, ethical justification and a transparent public process to solicit and incorporate stakeholder input. In the interim, the organizations encourage governments to permit and to fund work like Mitalipov’s that investigates the potential of human germline engineering.

Having been a part of this group, I can attest that we thought long and hard about this aspect of the statement, and that we made it despite our concerns that this technology holds risks for both individuals and society, including the potential to increase existing inequities in health and quality of life. We may try and regulate use and norms such that we get the upside and not the downside, but we must acknowledge that to a large extent the two are inextricable.

Speaking only for myself, I can say that I see the allure of a form of intervention that might prevent rather than merely treat sickness and suffering, even as I sympathize with those who worry about the impact of the technology on future generations. If the choice were mine, it would be a difficult choice. But in the end, what I recognize is that we are not given a choice between going backwards and going forwards. The truth is that gene engineering is going to happen. No one government or individual is going to stop it — the world is too big and the stakes are too large. The questions that sit in front of us are not yes or no, but where, how and under what circumstances. I believe that a thoughtful society should engage with the technology, providing capital and oversight, resources and regulation. To turn our back is to sacrifice whatever leverage we could bring to bear as we establish norms for use, and to cede our leadership role in the scientific community at the dawn of an era, the start of a journey to…wherever.

Follow me on twitter!