Autonomy has been a core guiding ethical principle of genetic counselors pretty much since the profession’s founding in the early 1970s. There are various definitions of autonomy but on a work-a-day basis in genetic counseling, it is usually conceptualized as the right of patients to make decisions about genetic testing that are educated and without undue external influence or pressure. It relies heavily on information-based consent. It is often, though not exclusively, evoked in the context of reproductive decision making, such as choosing whether to have children, whether to undergo prenatal testing and which test to have, and whether to continue a pregnancy if a fetal condition is diagnosed.

Reproductive autonomy in the context of genetic counseling was seen as an antithetical counterpoint to the Anglo-American-Germanic eugenic ideology of the first half of the 20th century and consistent with the wider trend in medical care to be patient-centered. But in a table-turning move, reproductive autonomy is now being used as an ethical justification for offering what many have called a modern version of eugenics – preimplantation polygenic screening of embryos for traits such as IQ, height, and eye color. I am not going to name the companies offering the testing because they don’t deserve or need the advertising. But the basic argument they make is that parents have an autonomous right to have children with the kind of traits that parents desire. Some people choose reproductive partners on this basis, so how is that any different than using a polygenic score?

The space between a trait and a mild medical condition, and between a mild versus a serious medical condition, is full of shades of gray but some of the traits that polygenic embryo testing screens for are clearly not medically signfiicant. Autonomy, as currently conceptualized, is unclear about which tests for which traits or medical conditions should be available to prospective parents or what ethical principles should guide parental choices.

Let me make my biases clear. I have a lot of criticism of preimplantation polygenic embryo screening. I don’t think that patients, children, or society benefit from the ability to select for these traits. The predictive value of polygenic screening for the traits is limited and questionable. And even if testing were reliable, is it worth tens of thousands of dollars to have a blue-eyed kid who is an inch taller and has an IQ 7 points “higher”? It almost sounds like a scam because parents will never know if their bundle of eugenic joy truly is taller or “smarter” than if they had just rolled the gametic dice.

I am also not convinced it will ever catch on to any large degree. Sure the ultra-wealthy can well afford it but IVF is a physical and emotional bear to go through (Note to those who push IVF on their partners) and a live birth often requires multiple cycles of embryo transfers. To say nothing of the higher incidence of pregnancy and neonatal complications associated with IVF, which is not entirely explained by parental characteristics. I also don’t like how preimplantation polygenic embryo screening has been subtly legitimized by giving it a set of initials: PGT-E (for preimplantation polygenic testing of embryos, just like PGT-A (for preimplantation aneuploidy screening), PGT-M (for monogenic conditions). Identifying something by its initials suggests that it is a common and widely accepted practice, which preimplantation polygenic embryos screening definitely is not.

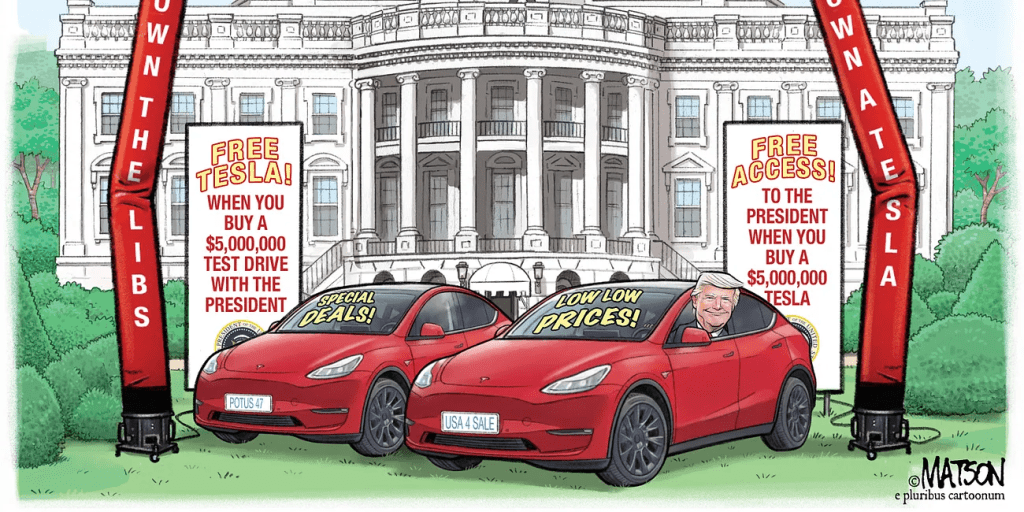

Really, the threat to society is not preimplantation polygenic testing. The more serious threat is that a bunch of garden variety jerks with unimaginable wealth and power will raise a new generation of even wealthier and more powerful jerks who think they are privileged and God’s gifts to humanity. Someone should develop a polygenic score for being a jerk.

But back to the autonomy issue. Until now, challenges to autonomy stemming from which conditions should be available for prenatal testing have been raised before. Is it ethically acceptable for deaf couples to select for having a deaf child? What about a couple with achondroplasia choosing to terminate a pregnancy in which the fetus was of normal stature? These scenarios, not particularly common in clinical practice, were often evaluated from an ableist bias. Back in the 1980s, when amniocentesis and CVS were the only means of reliably determining fetal chromosomal sex, there was a general taboo against prenatal testing strictly for this purpose. This was a partially racialized ethic; not uncommonly, in the US the taboo was invoked in the context of Chinese or Indian parents but not typically for non-Asian parents who were nominally undergoing prenatal testing for “parental anxiety.” Now that fetal chromosomal or anatomical sex can be determined early and reliably in pregnancy, the ethical discussions seem to have been pushed aside because, well, I guess that information is now considered “fun” or “practical.”

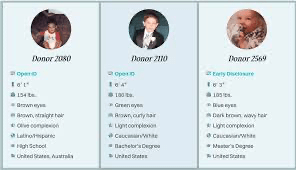

Preimplantation embryo polygenic screening to select for non-medical traits is, to some extent, a natural extension of the way that people have been choosing gamete donors for decades. Gamete donor profiles include a bewildering array of (usually unverified) donors’ non-medical traits such as demographics, educational attainment, reading preferences, and employment. This may in part be driven by patients’ emotional desire to choose a donor who might have the characteristics of person that the patient would have chosen to have a baby with if gamete donation was not necessary. But there is also an element of hoping that these traits might have a genetic basis and thus the child might share some of these same traits.

In the context of preimplantation polygenic embryo screening, the argument is made that patients are informed about the limitations of the predictive ability of polygenic testing and they are making knowledgable choices free of external direct pressure. For the moment putting aside the argument that commercial for-profit companies may not provide unbiased information and that there could be a certain amount of sales pressure, this is pretty much the same ethical justification used for any prenatal test. One ethical justification to rule them all. Although many of us may have the gut reaction that polygenic embryo screening is just plain wrong, there is little in this practice that violates the common conceptualization of autonomy.

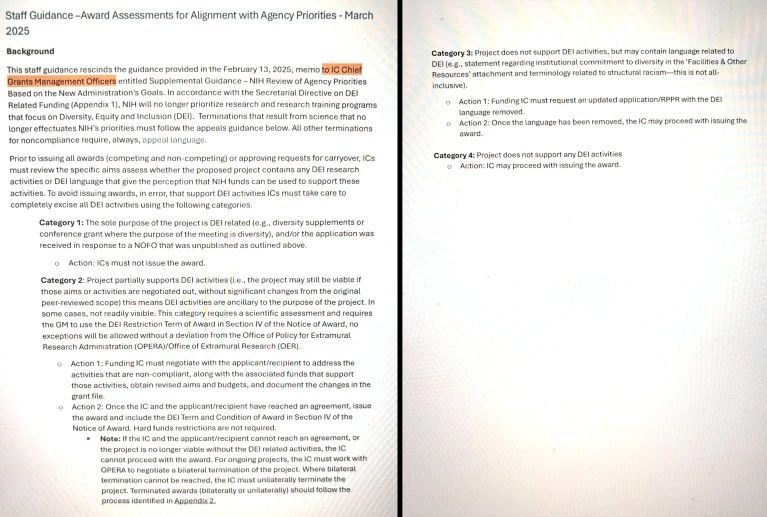

In a challenge to the traditional conceptualization of autonomy, Ainsely Newson, Isabella Holmes, and their colleagues from the Universities of Sydney, Melbourne, and New South Wales recently offered up a different take on reproductive autonomy, a model that addresses some of the issues I raised above.* They delineate a conception of autonomy characterized by four attributes – qualtitiatve, relational, institutional conditions, and weakly substantive. These are outlined below, along with some thoughts on my part of how they might apply to preimplantation polygenic embryo screening.

- Qualitative – the number of options offered to patients is less important than the quality of those options. Those options should be presented in ways that are consistent with patient values and such that patients are aware of the limitations of genomic testing in predicting what it means for their offspring. It requires good counseling skills to explore with patients what the traits in question mean for their lives and to what extent preimplantation polygenic screening of embryos reliably results in the promised outcomes. It also suggests that genetic counseling should not be performed by entities who have a financial stake in patients’ decisions. No criticism of the hard working, highly ethical genetic counselors, physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals who work for these companies, but, from a patient standpoint, a third party may be a preferable source of information.

- Relational – No one exists in a social vacuum. Everyone is embedded in a social and economic context that can impact decision-making. Wealthy parents who are highly educated and have extensive resources may feel social and familial pressures to have children with traits that are presumably related to wealth and education. Conversely, less advantaged parents may feel pressure to offer their children as many biological advantages as possible, which they might think include higher IQ or being taller. Eye color? Well, that’s pretty much ethnically embedded. And everybody faces the pressure of having “a healthy baby,” a pressure intensified by advertisements that genetic testing helps assure a healthy baby.

- Institutional Conditions – Patients need equal access to affordable health care, control over decisions about when and where to have children, and medical, educational, and financial resources. If everybody has equal access access to the same resources, then a test that predicts an inch of height or a few IQ points is less useful if the appropriate environment will have the same or even better effect.

- Weak Substantivism – The process of how a patient makes a decision is less important than how it reflects the normative substance of the decision. In the context of preimplantation polygenic embryonic screening, the normative decision – “the right decision” – may be to have blue-eyed taller, higher IQ children, as imposed by the norms of a White Eurocentric majority. If instead a decision is made that is consistent with patient values rather than strong normative pressures, then it is weakly substantive.

The article is not an easy read for those of us less conversant with the bioethics literature; I had to read it a few times to get a handle on it. I freely admit I may have misconstrued some of their ideas and stand open to correction. But it is an excellent starting point for revisiting the concept of reproductive autonomy in the context of genetic counseling and how the concept of autonomy needs to be relevant to the current genomic universe.

Maybe too we should think about other ethical principals to consider in addition to autonomy. Complex decisions require complex ethics (I will leave that one for bioethicists and the Good Readers of The DNA Exchange to debate). We are living in the 21st century, not the 20th century. And God knows the world does not need eugenics.

_________________________________________________

- The Holmes et al. paper use the term pregnant agent to refer to the pregnant person. This makes sense in the context of their ethical arguments about who has agency to make decisions about pregnancy and the complexities of who can carry a pregnancy and how pregnancy can be achieved.