I am in the midst of watching the Jeux olympiques d’été de 2024 (aka The Paris Olympics, the XXXIII Olympiad), one of the benefits of retirement. As I write this, Rowdy Gaines is narrating a swimming event with his usual infectious and unconstrained enthusiasm (every country has its own Rowdy Gaines equivalent for various sports). Watching the marvelous bodies and performances of these athletes triggered some thoughts about which bodies are or are not allowed to compete. More specifically, I began reflecting on the history of using genetic testing to determine which athletes would be permitted to compete in women’s Olympic sporting events. It’s a tale of how the inappropriate use of genetic testing can have far reaching ethical, political, legal, social justice, sexual bias, and racial bias effects.

There is wide agreement that elite biological male athletes generally have superior physical performances compared to elite biological female athletes in some sports. It is an understatement to say that evaluating athletes to determine if they are “female enough” to compete as women is highly controversial, including among athletes themselves. I am not going to enter that fray here. The problem is that biological sex is more of a spectrum than a duality.* The pegs of our bodies come in many shapes but the sports world – and society at large – tries to squeeze these multiform and at times changing pegs into either square holes or round holes.

The concern about athletes’ sex goes as far back as the original Greek Olympic Games, when athletes performed in the nude. One theory posits that the requirement of Greek athletes to perform au naturel, was motivated by Greek admiration of the male body and to avoid the possibility of a male athlete competing as a female. This is based on the story of Kallipateira of Rhodes, who was caught posing as a male so she could train her son in boxing (females were not allowed to be trainers in the 5th century BC though they could participate in some events), after which trainers were also required to be naked.

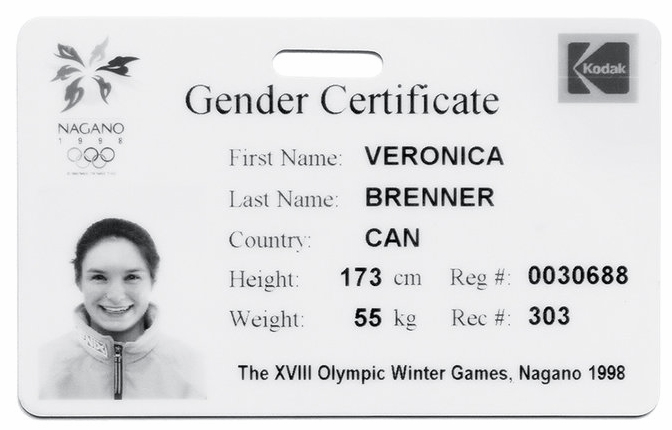

The story picks up again in the 1930s with worry about “sex posers” in the Olympics, even though there has never been a documented case where a male knowingly disguised himself as a woman to compete in an Olympic event (though some athletes later proved to be intersex). Mostly the suspicions came from men who thought certain women didn’t look feminine enough. Between the 1930s and 1960s, there are several reports of a few athletes in various athletic competitions for women who were suspected of being biological males. This also played out during the Cold War, with Western suspicions of the “true sex” of some high performing Eastern Bloc athletes competing in women’s sporting events. In the 1960s, the International Amateur Athletics Federation (now called World Athletics), in cooperation with the International Olympics Committee (IOC) instituted a policy that required women to undergo a physical examination by (usually female) physicians to verify their biological sex, what athletes disparagingly called “naked parades.” Until the late 1990s, females could compete as women only if the IOC Medical Committee had issued a Femininity Certificate, also called a Gender Certificate.

They lined us up outside a room where there were three doctors sitting in a row behind desks. You had to go in and pull up your shirt and push down your pants. Then they just looked while you waited for them to confer and decide if you were OK. While I was in line I remember one of the sprinters, a tiny, skinny girl, came out shaking her head back and forth saying. ‘Well, I failed, I didn’t have enough up top. They say I can’t run and I have to go home because I’m not ‘big’ enough.

American shot-putter Maren Sidler’s description of a a “naked parade” from the 1967 Pan American Games in Winnipeg, quoted in Heggie V. Testing sex and gender in sports; reinventing, reimagining and reconstructing histories. Endeavour. 2010 Dec;34(4):157-63. doi: 10.1016/j.endeavour.2010.09.005. Epub 2010 Oct 25. PMID: 20980057; PMCID: PMC3007680

Genetics entered the picture when the IOC Medical Committee introduced Barr body testing into the mix in the 1960s. In 1949, University of Western Ontario researcher Murray Barr and graduate student Ewart G. Bertram published a paper in Nature in which they demonstrated that, by using a simple staining technique, the chromatin of a cell’s inactive X chromosome in individuals with two X chromosomes could be identified with a microscope. In a methodology that might be ethically questioned by some today, Barr used feline neural cells obtained by brain biopsies of anesthetized cats. As every student of genetics knows, one X chromosome stays active and the remaining X(s) is inactivated in individuals born with more than one X chromosome. And, as every student of genetics knows, Barr body analysis is a less than perfect indicator of biological sex. Nonetheless, the IOC chose to use this analysis to determine who could or couldn’t compete in women’s competitions. It was a relatively easy test to perform at scale using buccal cells or (ouch!) hair bulbs.

Starting with the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, the IOC randomly tested some female athletes using Barr body analysis and sometimes Y chromosome fluorescence studies. In the 1968 Mexico City games, Mexican geneticists Alfonso León de Garay and Rodolfo Félix Estrada organized a large scale genetic testing program of 1,265 Olympic athletes and perform a wide array of genetic, cytogenetic, and familial studies in an effort to study the determinants of athletic ability. Their analysis included karyotyping but those specific results were not made available so it is unknown if any athletes were disqualified and how many actually underwent sex chromosome studies. By the 1972 Sapporo games, genetic testing of female athletes became mandatory (except for Princess Anne, sister of Queen Elizabeth, who, when she competed in equestrian events in the 1976 Montreal games, was given a pass on undergoing sex testing). Barr body analysis +/- Y chromosome staining continued until 1992, when they were replaced with SRY and/or DYZ1 PCR studies. As with Barr body and Y chromosome studies, SRY and DYZ1 status are also less than perfect predictors of biological sex. Some athletes “passed” Barr body testing in one Olympics only to “fail” the PCR test in a later Olympics. Sometimes you were female, and sometimes you weren’t, depending on the whim of the the rule makers and the available genetic technology.

Official reports of the Olympics used various names to refer to these genetic tests over the years: sex checks, sex control, femininity tests, femininity testing, femininity control, gender verification, gender testing, gender tests, and sex checks. Sometimes names fell into disuse only to resurface years later. This illustrates how changes in language norms often do not follow a straight-line trajectory, as well as confusion about distinctions between sex and gender, and just what it is the rules were trying to get at.

It’s unclear how many individuals were excluded from Olympic participation based on sex verification testing because the IOC didn’t always reveal that information and they wished to protect the confidentiality of the athletes, but apparently very few athletes were actually excluded, even if they “failed” the tests. Of course, some athletes may have been excluded by testing in their home countries before they were allowed to go to the Olympic Games and some Olympians may have quietly bowed out before the start of the Olympics if testing at the Olympics didn’t qualify them as women. By 1999, the IOC abandoned mandatory sex testing.

There are more instances of exclusion based on sex testing in non-Olympic competition, several of which received extensive and at times sensationalized media attention. In particular, some athletes were identified with differences in sexual development , and these athletes continue to pose the most controversial, challenging, and contentious situations for sports regulatory committees, athletes, the media, and the general public. Some intersex athletes were unaware of their conditions prior to testing. It’s tough enough explaining this information within the context of a genetics clinic to someone for whom there was at least a suspicion of an intersex condition. Imagine finding out for the first time just before a major athletic event and then sometimes having that information broadcast around the entire planet. Some athletes experienced serious psychological problems as a result.

Some in the genetics community expressed concerns about the use of these tests almost immediately. The objections raised by Albert de la Chapelle, Malcolm Ferguson-Smith, and the Singapore pediatrician/geneticist Wong Hock Boon, among others, were largely ignored. The Social Issues Committee of the American Society of Human Genetics also issued a report criticizing the use of genetic testing in sports. It’s unclear how much these objections influenced IOC policies. The IOC seemed to react more to social and media pressure than the opinions of physicians and scientists.

The IOC abandoned mandatory sex verification in 1999 and after two decades of changing rules recently produced a more fair-minded and inclusive policy following the Tokyo Olympics in 2021. However, the IOC leaves it up to the governing bodies of individual sports to determine who can compete as a woman. Many of these individual governing bodies use athletes’ testosterone levels to determine eligibility, as does the Women’s National Basketball Association and the National Women’s Soccer League in the US. Thus athletes such as Mokgadi Caster Semenya, Francine Niyonsaba, and Christine Mboma have been identified as intersex, and in some cases have been told they need to to undergo ethically questionable medical interventions such as gonadectomy or testosterone lowering drugs to compete in certain events. This can take deep physical and psychological tolls on interesex and transgender athletes, the ones who probably suffered the most from sex verification testing in athletic competition.

The general justification offered for sex verification testing is to level the competitive playing field. That is understandable and many athletes likely support that general concept. Fair compeition is, after all, why performance enhancing drugs are banned. However it is interesting that genetic testing was only offered for X or Y chromosomal material. There has never been routine testing for autosomal genes, such as some alleles of the EPOR gene, which can give an edge in marathon type sports by allowing the blood to carry more oxygen. The Finnish cross country skier Eero Antero Mäntyranta won 7 medals in 3 Olympics, possibly aided by his diagnosis of primary familial and congenital polycythemia (ironically he later tested positive for amphetamine, a performance enhancing drug). Although all of the genes linked to athletic ability have not been identified and is likely the result a complex interplay of many genetic and environmental factors, I am pretty sure the genomes of LeBron James, Katie Ledecky, Diana Taurasi (one of the most complete basketball players I have ever seen), and Lionel Messi look different than a lot of their competitors’ genomes, not to take anything away from these athletes intensive training regimens. But we don’t classify athletes by genotype – unless of course that genotype is related to biological sex.

The misuse of complex genetic information also occurs in non-athletic situations – MTHFR polymorphism testing, polygenic scores calculated for IVF embryos, ancestry testing to justify white supremacy, to name a few. No matter how hard geneticists try to shape the public conversation about genetics, once the CATG is out of the genetic bag, we have very little control over how it is reported, used, and misused. It plays out in social, political, legal, and ethical landscapes in unpredictable and at times harmful ways. It’s not merely a matter of better education of the public and various authorities. How genetics and other scientific information is used is shaped by prevailing ideologies, politics, and diverse cultural values. And sometimes by narrow-minded hate.

_______________________________________

- – My favorite example of the non-duality of life is the green sea slug, Elysia chlorotica. In its juvenile stage it is brown with white spots and looks like, well, a slug. It seeks out specific algae –Vaucheria litorea – for food, and sucks out the algal cell’s contents, including the chloroplasts. The snail no longer needs food at this point, getting all of its energy from photosynthesis via the algal chloroplasts it ingested. Not only that, it transforms its morphology such that it eventually has a slug head but its body color changes to green and looks for all intents and purposes like a leaf, complete with veins. I first learned about E. chlorotica in The Light Eaters, Zoë Schlanger’s fascinating book that will challenge your ideas about plant life. Oh, and by the way, along the lines of trying to define biological sex, a green sea slug produces both sperm and eggs.