Polygenic risk scores* are all the rage these days. Thousands of articles and research studies have attempted to link polygenic scores to just about every medical condition, behavior, and trait you can think of, and a few I had not thought of such as reproductive behavior. They have contributed to improving our understanding of human genetic architecture, hold potential for guiding treatment decisions, and have started to open the black box of gene-environment interplay, to name a few applications. Polygenic scores have laid bare the racial/ethnic bias in genetic data bases that have proven to be overwhelmingly comprised of people of Northern and Western European ancestry and shamed the genetics community into striving to better serve all communities. They have also been used inappropriately in clinical practice, such as with preimplantation genetic testing to predict potential height and intelligence of an embryo (quite poorly as it turns out) to determine its “implant-worthiness.”

The value of polygenic scores in clinical settings, despite the optimism expressed in many of the publications, remains unproven for the most part. Time and more research will presumably filter out the clinical winners from the losers. But we also need to sort through the thorny ethical, economic, and social justice issues with equal intensity and resources.

One particular application of polygenic screening is undermined by a naïve understanding of human psychology and a failure to learn from past experience in genetics – population polygenic screening for common conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer. I don’t believe that polygenic scores will have a particularly strong impact on reducing the impact on morbidity and mortality from these common conditions. There is ample evidence that genetic testing has little or no effect on risk-reducing behaviors. In fact, I’d go as far to say that the research investment into population polygenic screening for these conditions is disproportional to their likely medical benefit.

The aim of polygenic screening for health conditions is to produce a number, some likelihood that a healthy person will eventually develop condition X, and that risk estimate would be the basis of medical recommendations to reduce or manage the risk. As with all likelihood estimates in clinical care, polygenic screens, with or without inclusion of demographic and clinical variables, will be imperfect, maybe slightly more or less imperfect than estimates derived by other means. Genetic counselors have been dealing with such numbers since we first entered clinics half a century ago and began providing patients with empirical recurrence risks for genetic conditions or the probability of having a baby with an aneuploidy based on parental age or screening results. Some think that providing numbers is the purpose of genetic counseling but it turns out to be only the beginning of the counseling session (emphasis on counseling).

The naïve assumption underlying polygenic screening for common conditions is that the risk number will magically motivate people to undergo more frequent colonoscopies, breast MRI, change their diet, stop smoking, exercise more, and reduce the stress in their lives. Yeah, well, good luck with that, at least on any large scale, on a sustained basis, and outside the context of a research study of self-selected participants conducted over a short time span. Sure, some people will be nudged into screening uptake or lifestyle changes, and a smaller percentage may even keep it up. But decades of experience have shown that most people are going to continue doing what they are doing with their lives – healthy behaviors or not – thank you very much.

There is a persistent but mistaken view in genetics, and medicine in general, that the human psyche is an objective statistical risk calculator and the “right” number will motivate people to do the “right” thing. This is a zombie concept that, like nondirectiveness, refuses to die. But the human mind is a complex and not entirely rational system, at least not like a Sherlock Holmes ratiocinative detective type of rationality. Numbers are embedded in a patient’s psychological, emotional, life-history, social, economic and political matrix that can vary over the short and long term. Numbers are interpreted or misinterpreted or denied or ignored such that it fits into the patient’s elastic view of the world. The results are often decisions that seem to make no sense or appear ludicrous to medical professionals but makes perfect sense to patients at this point in their lives. That decision could change over time, sometimes for apparent reasons such as the death of a family member, and sometimes for no obvious reason. They can even change from a “good” decision to a “bad” decision.

Of course, some people seem to be nominally objective decision-makers, the so-called engineer or statistician types. The patients who suddenly become actively engaged in the genetic counseling session once numbers are tossed out for discussion, dissecting and closely questioning their accuracy, how they were derived, and what the confidence intervals are. If you bring up statistical measures such as area under the curve or Cox proportional hazards, they even seem mildly sexually aroused. But the engineers and statisticians ultimately interpret numbers psychologically, just like the rest of us.

I don’t mean to imply that polygenic scores are totally useless. One of our jobs in medicine is to find ways to reduce the impact of disease on patients’ lives and polygenic scores might provide some help to that end. Research into polygenic traits can contribute to the scientific understanding of human and medical genetics. And polygenic scores will likely have some clinical utility. I can see some settings where a health risk has already been identified and a polygenic score can help further refine that risk. For example, polygenic scores might modify the ovarian or breast cancer risk or the age of onset in a patient who carries a pathogenic BRCA1 variant. It could then influence timing of risk-reducing surgeries or help determine if such surgeries are even necessary. Readers can undoubtedly think of other scenarios where polygenic screens might help influence decision making by high risk or affected patients.

The claims about polygenic scores are like a historical replay of the HLA story. During the 1970s, the HLA system was found to be associated with a wide range of conditions and many researchers were predicting HLA testing would be useful in disease prediction (I was even briefly involved with such a study in the late 1970s). As it turned out, HLA was not particularly useful for disease prediction on a clinically meaningful scale, although studying the HLA system has produced a number of other benefits That being said, there are outrageous applications of HLA testing currently available, such as using HLA typing to determine if a couple are “genetically” attracted to each other.

We need to scale back expectations that population polygenic screening will significantly reduce the morbidity and mortality stemming from common conditions. I suspect that its impact on disease and death will be modest and at times unclear, perhaps with an occasional success story. The minimal research that has been done to date on the uptake of screening or other medical recommendations after a polygenic screen have produced mixed results and are not overwhelmingly convincing, though of course further research may prove otherwise.

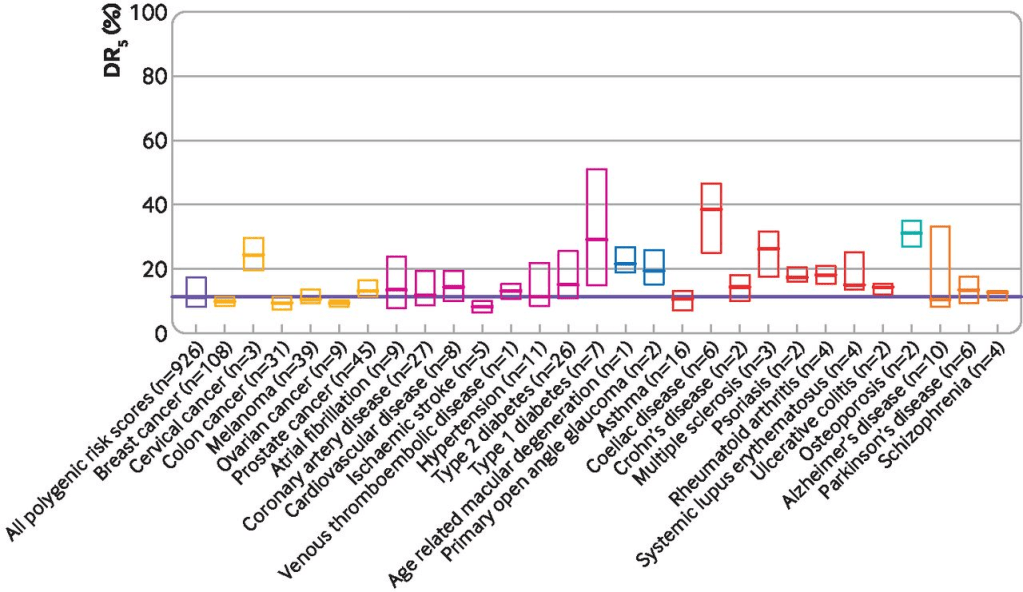

There are also technical reasons to suspect that polygenic screens may not work well on a population level as measured by detection rates, false positive rates, and positive predictive values. In addition, existing inequities in access to and utilization of health care will further reduce the utilization of polygenic scores and subsequent follow-up of medical management recommendations by patients. If you don’t have access to good medical care and the appropriate interventions, or you can’t pay for it, or you have a lack of trust in the system, what good is screening?

We need to take a hard look at just what we expect to achieve with polygenic scores. A lot of energy, resources, and finances go into research and publications about polygenic screens. Perhaps that time and money could better be directed to research where benefits of polygenic testing are more likely to be realized or to other areas of genetic research altogether, like how and why people make decisions about healthcare and how it is affected by personal, economic, social, historical, and political factors (think Covid vaccination uptake).

The medical genetics community may be resistant to my recommendations. Some of that resistance will be based on thoughtful and understandable disagreement with my opinions and their own assessment of the potential of polygenic scores in a population setting. But underlying some of that disagreement, and some of the enthusiasm for polygenic scores, is that all the players in the genetic testing game have blind spots and conflicts of interest. Researchers in the academic/clinical research industrial complex need grants and publications to further their careers. This includes not only Principal Investigators, but also the many other people necessary to conduct research – ethicists, research assistants, junior investigators, etc. The genetic counseling profession has for better and worse taken up genetic testing as its defining role in the medical system, and genetic counselors working in direct patient care demonstrate their economic worth to their employers by increasing the downstream revenue that results from genetic testing (revenue raised directly by genetic counseling alone is rarely enough to cover salaries and benefits). Commercial laboratories make their money by selling genetic tests; not a bad thing in and of itself but it can cloud one’s views. With all these players all talking the same game, they can lose sight of what’s good for the fans and unintentionally prioritize what’s good for the teams, such as citing improving institutional revenue from increased imaging as one of the benefits of polygenic scores or direct-to-consumer commercial labs offering polygenic scores when the health benefits remain at best unclear. I am not suggesting that researchers, genetic counselors, and labs are unethical and I am not questioning their dedication to quality medical care for patients. They are just being human and the human mind has a way of persuading itself that it’s doing the noble thing when in fact it may be putting its own interests first.

People interpret numbers how they want to interpret them. We see evidence of this on a large scale every day. Climate change is ignored in the face of rising temperatures and melting ice packs. Election results are denied because they don’t conform to the desired outcome. Millions of pandemic deaths are explained away as falsified or manipulated numbers to justify disregarding public health measures. This holds equally true for the results of genetic testing in populations. If we want genetic testing to be useful to our very human patients, we must develop a more sophisticated and less naïve understanding of the human psyche.

__________________________________________________

* – There is some controversy about the name “polygenic risk score.” “Risk” tends to evoke anxiety in our minds; typically, one is not at risk for good outcomes, like winning a large lottery prize. It also implies a value judgment on the condition being screened for. Many people would argue that deafness or autism are desirable or normal outcomes, not something that one is at risk for. Alternatives include “polygenic score” or “polygenic index.” I like my own coinage – “polygenic screen” – when referring specifically to polygenic risk scores for medical conditions in healthy people since it implies the test is not diagnostic (yes, I know, people tend to confuse diagnostic tests with screening tests à la NIPT). In this posting, I use all these terms more or less interchangeably because, well, I can’t make up my mind which I prefer.

In order to distinguish between the various applications of polygenic scores, consider these suggestions for a possible terminology:

Polygenic Index – when used to predict a non-medical trait, such as height or intelligence.

Polygenic Screen – when applied to population screening for common medical conditions.

Polygenic Risk Score – when applied to a population previously identified as being at high risk for, or affected by, a medical condition, such as breast cancer, to potentially guide treatment, risk reduction, and surveillance recommendations.

To distinguish between a polygenic only model and a model that combines SNP analysis with clinical and demographic factors, a “+” could be added, e.g., Polygenic Screen+– Breast Cancer to denote a breast cancer risk prediction model that incorporates SNP analysis with the Tyrer-Cuzick or other breast cancer risk prediction model.