This spring we will welcome a record number of new genetic counselors to the field. Based on 2022 year Match data from the National Matching Service Inc, we expect >500 new graduates in 2024.* The growing number of graduates is the natural result of more training programs and expanding class sizes in existing programs.

Unfortunately, it seems that this record number of new grads arrive to one of the worst job markets for genetic counselors in many years. Based on conversations I have had with a number of recent or soon-to-be genetic counseling graduates and informal conversations with several genetic counselors involved with training program administration, many new grads are having a hard time finding that first position. It is really tough for job seekers right now.

I am writing this to provide some historical background about why we might be in this position, and where we have so missed the mark in terms of supply and demand. It is my hope that we can learn from these mistakes and make changes as a profession to improve job opportunities, growth and security while also improving genetic services.

I am also writing though because I want to give assurance to all those entering the field in 2024 that it will get better. When I graduated, 20+ years ago I came out of my training program without a job, and I know how devastating and heavy that can feel. The job market has waxed and waned in the past and the pendulum will swing the other way at some point. The reason for my optimism is that, although our current job boards don’t reflect this, I believe that now, more than ever there is a need for the expertise and services that we can provide as genetic counselors. I want to reassure you that you will one day find that perfect job. And I also want you to know that the fact that you don’t yet have a job yet is not your fault.

How did we get here?

Recent history provides context for how we got to this point. Just over a decade ago, three major events rocked the field of clinical genetics:

- Although it is hard to believe that there was a time before next generation sequencing (NGS), Sanger sequencing was the standard for many years. NGS allowed for gene sequencing to be done more cost-effectively and around 2010 we started seeing more multigene panels come to the market.

- In late 2011 the first prenatal cell-free fetal DNA screening test, MaterniT21, became commercially available through Sequenom. In the years that followed, versions of cfDNA tests were released by multiple companies, creating an intensely competitive commercial landscape.

- In June of 2013, Myriad Genetics lost their monopoly on BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that human genes could not be patented in the landmark case, Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics. This opened an opportunity for many labs to enter the genetic testing market.

All of these factors contributed to an enormous growth of the genetic testing industry and rapid escalation in demand for genetic counselors. The commercialization of the field of genetic testing was unlike anything we had seen before. Genetic testing was front page news and investors were lining up to be a part of it. Labs, flush with venture capital money, created many new job opportunities for genetic counselors.

In some cases, the job creation was very direct, with labs hiring genetic counselors as medical science liaisons, or to work in variant interpretation, product development and direct patient care roles. In other cases, the jobs created were with the telehealth companies labs hired to provide genetic counseling support to providers and patients ordering their brand of test. Additionally, the growing availability of genetic testing and investment in genetic testing technology created jobs in hospitals, clinics and research settings.

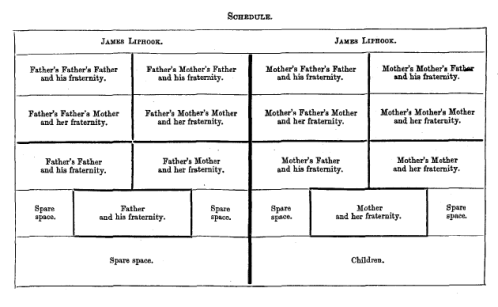

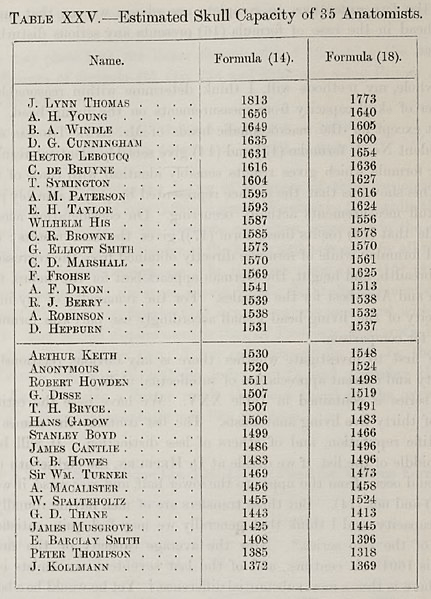

By 2015 it was clear that the demand for genetic counselors exceeded the number of trained people to fill the jobs. The following data was presented at the National Society of Genetic Counselors Annual Conference in 2015:

This graph contrasted the number of job postings on the NSGC job board with the number of genetic counselors coming out of training programs. In 2015, we had 291 genetic counseling program graduates compared to 655 job postings.

I am sad to say that this year, with ~500 graduates, there are 44 jobs listed on the NSGC job board at the time of this writing, and about half of these are not listings for genetic counselor jobs. In part, this reflects the fact that companies are not using the NSGC job board as their one and only means of recruitment, but it is also, undeniably, an indication that there are not many open jobs right now.

In 2015, a Workforce Working Group (WFWG) was established comprised of representatives from the American Board of Genetic Counseling (ABGC), the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC), the Association of Genetic Counseling Program Directors (AGCPD) and the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC). The charges to the WFWG were as follows:

● Identify current and future barriers and opportunities that impact the growth of the CGC workforce.

● Make recommendations to and support the development of specific action items that will facilitate growth of the profession and minimize and/or remove barriers to expansion.

● Drive and coordinate the efforts of the professional genetic counseling organizations to ensure the action items recommended by the working group are carried out in the most efficient and effective manner possible.

The WFWG commissioned a consulting firm, Dobson DaVanzo & Associates, LLC, to conduct a workforce supply and demand projection study of certified genetic counselors in the US over the time period from 2017-2026. This report considered many factors as they attempted to project the future needs and factors that could complicate their estimations.

The report developed two models in which the projected need for genetic counselors was 1 per 100K or 1 per 75K population and they projected we would reach equilibrium for the 1 per 100K model by 2026. While the workforce study recommended expanding existing training programs and developing new programs, they warned, “activities around this initiative will be focused on accelerating growth, while being mindful of not overreaching and exceeding demand.”

The report also raised concern regarding a “substitution effect” which was defined as other healthcare providers providing genetic counseling to patients. Additionally, the Dobson DaVanzo report also cautioned, “policies that restrict reimbursement to direct patient care by certified genetic counselors who are not affiliated with a commercial laboratory would likely reduce the effective demand for care, while at the same time reducing the ability of providers to meet patient need.”

This workforce report provided guidance on the importance of cautious growth with the caveat that it was an uncertain and rapidly changing landscape. The current situation has left me questioning if our profession considered this report in full as we have grown our workforce?

We met the Dobson & DaVanzo report’s projection of ~6.5K certified genetic counselors in March of 2023, more than 3 years ahead of schedule, and we continue to have more genetic counselors graduating from training programs than ever before. It does not appear to me that we have been “mindful of not overreaching and exceeding demand.” Of the 55 programs listed on the ACGC website, 14 are designated “new accredited programs”, and there are an additional 6 applications for programs in the works.

The substitution effect was defined by Dobson & DaVanzo as non-genetic counselors doing genetic counselors’ work. For the most part, we have not seen nurse practitioners, physician’s assistants or other providers stepping in to do the work of genetic counselors. From my view, what we have seen is that we are increasingly substituting ourselves. Let me explain. The labs understand that to compete in this market, it is essential to package genetic counseling with genetic testing. I see the labs going to providers who are neither equipped to nor interested in doing the counseling themselves, and offering complimentary genetic counseling as a perk for those ordering their brand of testing. The problem is, in many cases, genetic counseling provided gratis by a laboratory is not comparable to what would have been provided by a non-lab-affiliated genetic counselor in a clinical setting. The patient may get a message through a portal that tells them they can schedule a genetic counseling appointment. They may talk with a genetic counselor by phone for a few minutes to review results. What they rarely receive in these encounters is the comprehensive genetic counseling care that was factored into this workforce study. At this point, many providers and patients believe that this test-bundled follow-up care is standard genetic counseling. And, used to getting it for free, many providers and healthcare systems are now unwilling to pay what it costs to have genetic counselors on staff.

As important as it is, our profession has largely ignored the issue of how we are paid. This not only affects our job prospects, it affects the level of care we are able to offer to our patients.

The genetic testing lab bubble that began around 2013 created jobs funded by easy access to business loans and venture capital. Labs could use their huge investor funds to pay nice salaries to genetic counselors even when their companies were losing millions (and in many cases, hundreds of millions of dollars a year). The workforce study was developed at the time of this bubble and did not take into account the possibility that this job creation was unsustainable. Now, the VC bubble is deflating. After a decade of sustained and significant losses, investors are no longer willing to keep these labs going without return on their investment. Borrowing money has also become increasingly expensive and difficult. As a result, we are seeing labs retrench, close or be absorbed by competitors, with resultant layoffs of genetic counselors. And with many in our field looking for work, we have yet to reckon with the fact that we still don’t have a viable and sustainable funding model for genetic counseling services – in large part because fair reimbursement is difficult to demand when some version of genetic counseling services have so often been given away for free.

Another bit of history, and one the WFWG could not have factored in, was a global pandemic. Undoubtedly COVID-19 disrupted healthcare in ways that affected genetic counselors. As to the big picture, I think one important issue connected to the pandemic has been some of the financial challenges faced by many industries. For example the interest rate hikes, which have been a tool used to try to curb inflation has made funding more expensive and difficult to secure. The timing of this is unfortunate given the recent position of the labs. However, this does not change the fact that growing a profession on the basis of borrowed funds and start-up investors put us in a precarious place even without the added financial challenges brought on by the pandemic.

What comes next?

Given all that has changed over the last decade, and because we are nearly at the end of the period that the Dobson DaVanzo study had projected, I hope the WFWG has plans for another workforce study. Our profession is in need of an updated analysis of workforce issues.

Until we find a way to fund genetic counseling positions that does not rely on the house of cards that is laboratory funding, we should be mindful that our program growth does not outstrip the job opportunities for our newest colleagues.

The rapid growth in training programs suggests that the institutions involved looked at the rosy growth projections and ignored the recommendation to proceed with caution. Between the challenging job market and the difficulty securing clinical training sites for students, I imagine many involved in training programs are alarmed. While we have added many training slots, the program I attended, at Brandeis University, closed at the end of 2022 because there weren’t enough clinical training sites to serve the number of enrolled students the school required to cover the costs of maintaining the program. More programs may soon be facing tough decisions like this. One program director I spoke with shared, “many programs do not receive any state funding which means they have to run completely on tuition dollars. Even one student difference can break a budget that relies on those tuition dollars and may result in a program closing.”

In addition to considering carefully the growth of our profession through the training programs it is imperative that we all continue to advocate for fair reimbursement. The work we do as genetic counselors is valuable and crucial to the ethical practice of genetic healthcare, now more than ever. And I expect the need will only grow from here. But, we risk not being able to be in these roles, providing care and expert guidance if we do not first ensure that we have sustainable reimbursement for our services. Every single one of us needs to advocate for the “The Access to Genetic Counselor Services Act” so that genetic counselors are recognized by Medicare and can be reimbursed for the services we provide. This is everything. Have you contacted your representative?

I also hope we can mobilize as a profession to advocate for comprehensive standards of care in our work as genetic counselors. We should reflect on the recent challenges and disruptions we have seen in the field and consider how we are defining the practice of genetic counseling. If we continue to allow the profit motives of the labs to push us to act more as genetic testing facilitators, we will have an increasingly difficult time sustaining our ability to provide comprehensive genetic counseling and support.

Lastly I would like to send a message to all of the new and soon to be graduates who do not yet have jobs secured. Please don’t lose hope. You are the future of our profession, and we need you to help move us and genetic services forward for the better.

*The original version of this article stated, “A report published in 2022 by the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (ACGC) indicates that ~800 genetic counselors will complete their training at the 55 accredited training programs.” and referenced the following report: https://www.gceducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ACGC_2022_AnnualReport.pdf This was changed to reflect data from the National Matching Services Inc statistics, which reported that 547 applicants matched with a GC program in 2022.