by Jon Weil

Jon Weil was Director of the Program in Genetic Counseling, University of California Berkeley, from 1989 to 2001 and is the author of Psychosocial Genetic Counseling, Oxford University Press, 2000. He retired in 2001 but has remained professionally active. His current interests include the continuing development of psychosocial genetic counseling and promoting locally focused, patient-oriented international genetic counseling.

Countertransference, defined broadly with respect to genetic counseling, “refers to conscious and unconscious emotions, fantasies, behaviors, perceptions and psychological defenses that the genetic counselor experiences as a response to any aspect of the genetic counseling situation” (Weil, 2010). Countertransference is important because genetic counselors confront the hopes, fears, anxieties and behaviors of patients in many forms, both major and minor. It can be a source of understanding, empathy and improved clinical practice. It can also be a source of personal pain and discomfort, including anxiety about one’s clinical efficacy. The topic of countertransference is addressed in many publications, from several perspectives (e.g., Biesecker et al., 2019; McCarthy Veach & Redlinger-Gross, 2025). Nevertheless, a new perspective is potentially useful, as the following vignette demonstrates:

As I ended a presentation on Countertransference in 2011, a student approached me with a question – “Could you think of countertransference as prior probabilities?” My response was immediate – “That is one of the most interesting questions I have ever been asked”. With time, my understanding of the value and perceptiveness of his question has grown.

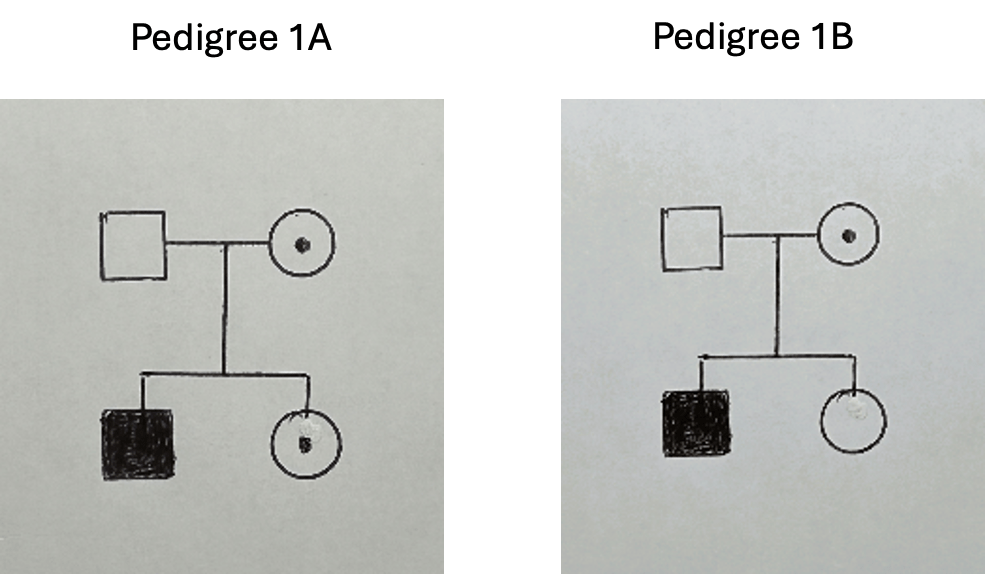

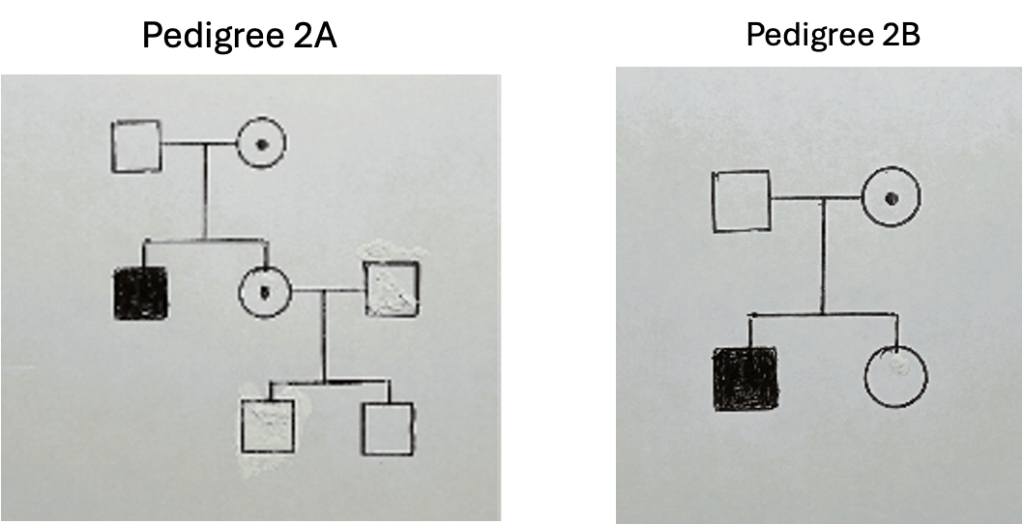

Bayesian analysis, to which the question referred, was critically important in clinical genetics and genetic counseling before DNA sequencing was developed (Hodge, 1998). Bayesian analysis uses “prior probabilities”, information that is subsidiary or “antecedent” to that presented in the counseling session, to adjust the calculated probabilities of the proband and/or other family members having a given genotype. For example, as shown in the following, the 50% probability that a woman whose brother has an X-linked disorder is heterozygous for the genetic variant (Pedigrees 1A and 1B; Table 1) is reduced to 20% by the additional, antecedent information that she has two unaffected male children (Pedigrees 2A and 2B; Table 2).

Table 1

| Hypothesis | 1A carrier | 1B non-carrier |

| Probability | ½ = 50% | ½ = 50% |

Table 2

| Hypothesis | 2A carrier | 2B non-carrier |

| Prior Probability | ½ = 0.5 | ½ = 0.5 |

| Conditional Probability | ¼ = 0.25 | 1 = 1.0 |

| Joint Probability | 1/8 = 0.125 | ½ = 0.5 |

| Posterior Probability | .125/(.125 + .5) = 20% | .5/(.125 + .5) = 80% |

A patient’s circumstances may also involve other forms of antecedent information. For example, for late onset disorders such as Huntington disease, the longer a family member lives without the onset of symptoms, the lower the probability that he or she carries the dominant genetic variant.

The parallels between prior probabilities and countertransference are intriguing. In psychological theory, countertransference involves experiences prior to the genetic counseling encounter that influence the genetic counselor’s cognitive and emotional assessment of the likelihood of potential interactions with the counselee (Weil, 2010). For example, a genetic counselor’s childhood experience with an angry parent increases awareness of a counselee’s growing anger during the course of a genetic counseling session. This in turn enables empathetic responses that reduce the likelihood of an angry outburst and promote a conversation that addresses the underlying issues.

However, it is when we look beyond these straightforward similarities that the broader heuristic value of the comparison becomes apparent. I believe there has been significant progress in promoting the value of countertransference in genetic counseling (Biesecker et al., 2019; McCarthy Veach & Redlinger-Gross, 2025). However, I assume that it still bears, to greater or lesser extent and in various settings, the onus of being a burdensome topic that, if not understood adequately, can lead to serious clinical errors and feelings of guilt and shame. Thinking of countertransference as antecedent information that adjusts the genetic counselor’s assessment of the probability of a patient’s possible thoughts or behaviors, thus improving the effectiveness of her or his interventions, provides another route to overcoming this onus.

Addressing countertransference can be difficult and distressing, bringing to consciousness painful experiences and emotions. These are best addressed with the assistance of an experienced supervisor or colleague or a licensed counselor or therapist. However, the analogy with prior probabilities allows some problematic aspects of countertransference to be reframed as issues of accuracy, reliability and representativeness:

There are a number of ways in which Bayesian analysis may produce erroneous results:

First, the data on which it is based may be incorrect and require subsequent revision (e.g., the diagnosis assigned to a forebear is incorrect, family understanding of the diagnosis is incorrect, and/or medical records are unavailable because they have been lost, are inaccessible in another country, etc.). Similarly, countertransference based on initial impressions or a specific attribute of the patient may prove incorrect or unreliable and require revision.

Second, the data may be used inappropriately. For example, for late onset disorders, age of onset data may be limited or not representative of the at-risk individual’s ethnicity. In the original formulation of transference and thus countertransference, it involved childhood behaviors and perceptions that offered the best solution to a difficult situation given the child’s position of powerlessness, but were less than optimal and could be significantly dysfunctional given that the adult’s situation is very different (Weil, 2010). Thus, we may compare countertransference grounded in perceptions and behaviors that are no longer relevant with Bayesian calculations based on data that are not representative of the situation to which they are applied.

Third, with complex pedigrees and/or multiple types of data (e.g., affected relatives and unaffected relatives with age of onset considerations), the calculation may be complex and one or more errors may have been made. Similarly, the complexity of a patient’s or family’s circumstances may induce countertransference that is not about the patient or family, but about the genetic counselor’s feelings of incompetence or of being overwhelmed, leading to responses that are not attuned to the circumstances.

The role of Bayesian analysis has receded and the understanding of countertransference has advanced since I was asked, a decade and a half ago, “Could you think of countertransference as prior probabilities?” However, thinking about countertransference in terms of accuracy, reliability and representativeness – as prior probabilities – may help reduce the anxiety and concern about making clinical errors that discussions about it, including in supervision, can evoke. It may help reduce the stigma that still attaches to countertransference, providing additional support for accepting it as a natural, inevitable process that is a potential source of valuable insight concerning the patient and the genetic counselor.

___________________________________________________________________

ACKNOWEDGEMENT. I thank Sahil Kejriwal for asking this very useful question.

____________________________________________________________________

REFERENCES

Biesecker, B. B., Peters, K. F. and Resta, R. (2019), Advanced Genetic Counseling: Theory and Practice, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hodge, S. E. (1998). A simple, unified approach to Bayesian risk calculations. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 7, 235-261

McCarthy Veach, P. and Redlinger-Gross, K. (2025) Genetic Counselors’ Personal Reactions and the Ethical Implications for Genetic Counseling Practice. In R. E. Grubs, E. G. Farrow and M. J. Deem (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Genetic Counseling. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 516-530

Weil, J. (2010) Countertransference: Making the Unconscious Conscious. In B. S. LeRoy, P. McCarthy Veach and D. M. Bartels (Eds.), Genetic Counseling Practice: Advanced Concepts and Skills. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 175-197

Hi Jon

Thanks for the thoughtful and well crafted piece. I think that if GC’s are aware/conscious of material that is grist for the mill for potential counter transference, it allows them to tap into the process of identifying issues behind clients/patients responses to various GC situations. I find that in GC training, countertransference gets a bad rap, as if the student was not present in the session, and hopefully columns like this one will give GCs permission to be more open to using the countertransference experience to better understand and respond/reflect to their patients.