by Misha Raskin

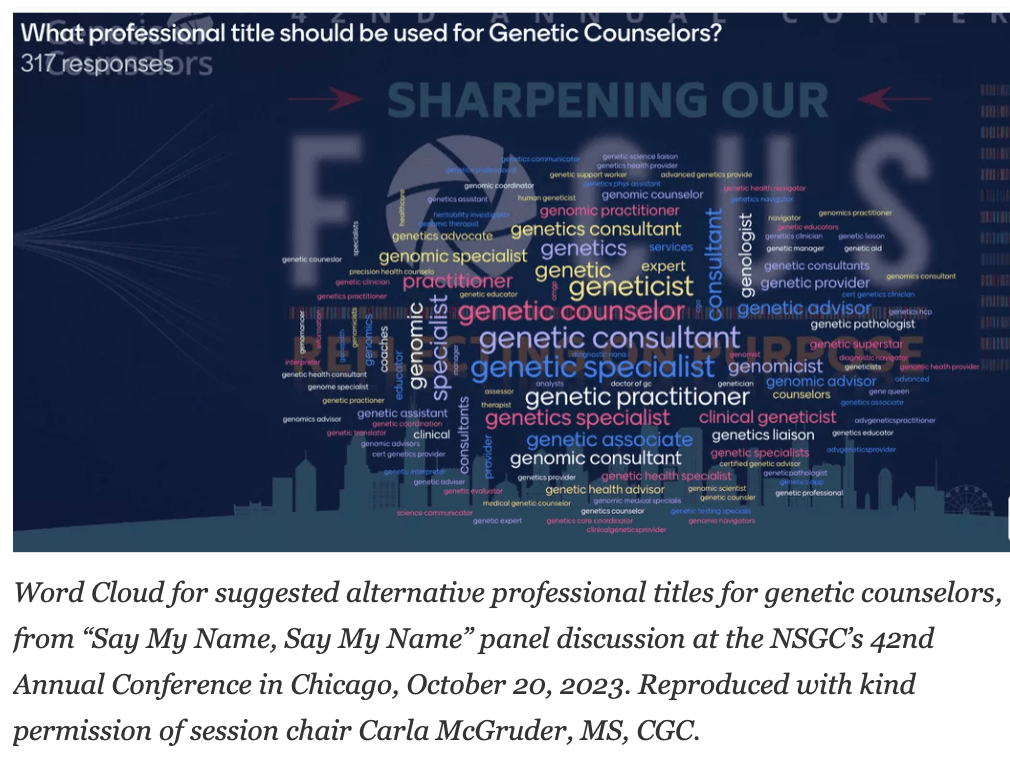

At the recent annual conference for the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) in Chicago, there was a spirited debate about whether or not to change the genetic counselor name. An alternate name was not presented, but below is a word cloud of proposed alternate names which DNA Exchange author Bob Resta shared in his recent blog post, where he decided to decline supporting a name change.

An informal poll that was circulated after the debate found that a significant percentage of genetic counselors were also wary of pursuing a name change.

For those who have not seen the debate, there were two primary tensions between the “pro change” side and the “pro same” side. The “pro change” side argued that changing our profession’s name could bolster NSGCs Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (J.E.D.I.) action plan (https://www.nsgc.org/JEDI), theorizing that possibly one of the reasons that genetic counseling is less diverse than many other professions is that our name creates a branding and recruitment problem. The “pro same” side brought up that if we genetic counselors change our name, then we’d need to update all of our state licenses, plus the language in our pending legislation to have Medicare recognize genetic counselors. Mr. Resta agreed that these issues were also an important factor to consider. The pro-same side also brought up that Physician Assistants are currently changing their name to Physician Associate, and that the associated cost of their name change is estimated at approximately $22 million, which would obviously be a staggering expenditure for an organization like NSGC.

Looking further at the “pro change” perspective, NSGC has rightly committed itself to implementing a successful J.E.D.I. Action Plan. Diverse teams provide better clinical care, better research, and build better businesses, all sectors where genetic counselors commonly contribute. Competing for diverse talent is in many ways the competition for the future. In a white paper published by the consultancy McKinsey in 2020, titled “Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters,” they outline the many ways that more gender and racially diverse organizations consistently outperform their less diverse competition, and argue for a greater focus on multivariate diversity (meaning “going beyond gender and ethnicity”). Currently, genetic counseling is among the least ethnically diverse fields in healthcare. We genetic counselors have an enormous amount to gain from a successful J.E.D.I. initiative. Over the long-term, perhaps far more than $22 million worth of benefit, if such a thing could be calculated. So, if strong evidence emerged that changing our name would substantially improve NSGCs odds of a successful J.E.D.I. program, then it’s prudent to consider this option with an open mind. We can’t just say that we’ll implement a J.E.D.I. program “unless it’s challenging or expensive,” right? If NSGCs J.E.D.I. initiative is a priority, then we should prioritize it. And maybe, there isn’t as much sacrifice as the “pro same” side implies.

Let’s also assess the state licensure argument more closely. There are lots of state licenses for all sorts of fields (see here and here for more info). Millions of people have state licenses all over the United States, including licenses for athletic trainers, auctioneers, and barbers, to name a few. So as a political matter, getting a state government to issue a professional license is often a manageable process. That’s why NSGC has approximately 35 state licenses. Importantly, a name change is drastically easier to navigate through a legislative body than a whole new license. Legislative bodies often use a “consent agenda” to take care of matters that are considered “technical and non-controversial.” It’s hard to imagine a piece of legislation that is more “technical and non-controversial” than changing the name on the genetic counselor license, as long as we don’t trigger a turf war by calling ourselves something like “doctor” or “geneticist.” In some states, we might even be able to get a name change done with volunteers, no lobbyists needed. And even in the states where we would need lobbyists and perhaps the consent agenda isn’t an option, this should not represent particularly expensive lobbying. If we genetic counselors decided to change our name, it would indeed require volunteer work to amend our state licenses, and it would have associated financial costs, but this is hardly an insurmountable hurdle – and one well worth jumping over to accomplish NSGCs Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion goals.

Next, let’s investigate the argument that a name change could hamper our efforts on Medicare recognition. Medicare is a massive and expensive federal program, and while there are different ways to calculate it, many legislators believe that recognizing a new provider, such as a genetic counselor, would represent a cost to a program that is already too expensive. So, unlike a state license, getting the United States Congress to recognize a new provider under Medicare is politically extremely difficult. In fact, after nearly two decades of effort, NSGC still hasn’t made any substantial progress on Medicare recognition, which in the context of this debate (and really only in the context of this debate), is actually a good thing. We haven’t even made it through the House or Senate. So, our lack of Medicare recognition at the present time argues in favor of exploring a name change, not the other way around, since our bill is still going through a process where amendments are common anyway.

To summarize, the benefits and costs of changing the genetic counselor title have not yet been fully flushed out. The debate at NSGC, while very thought provoking, was a starting-off point. We need to identify the best contender for an alternate name, and assess the benefits the alternate name is likely to generate. Perhaps the right name could both bolster the J.E.D.I. action plan and improve our prospects of gaining Medicare recognition, by better succinctly representing a genetic counselor’s value to the healthcare system. In parallel, we need to understand what the costs would be specifically for genetic counselors, as opposed to using Physician Assistants (I mean, Associates) as a proxy. PAs can already bill Medicare, have a different scope of practice, there are about 150 thousand of them in the United States, and there are likely many other differences. While their experience is of course informative, they are not a reasonable proxy. Once we have a better sense of what a name change would mean specifically for genetic counselors, then we can weigh the estimated benefits of the identified new name against the estimated costs. Importantly, when assessing the costs, we shouldn’t only ask lobbyists who expect to bill us for their services, as they have an obvious financial conflict of interest.

A successful J.E.D.I. program was always going to require substantial work, cost money, require new ideas, and require openness to meaningful change. Changing the genetic counselor name would indeed require NSGCs political operation to put in effort, but what is the point of having a political operation if we’re afraid to interface with the political system? If we can’t identify a new name that would propel NSGC’s J.E.D.I program, then it’s not worth the cost and effort. But I strongly support researching a new name further, and politically speaking, if we can’t handle a name change to a state license, then we can’t handle much of anything. And a name change may be easier than Mr. Resta’s charming idea that we convince George Clooney and a major network to launch a TV show about genetic counselors that’s as successful as the Sopranos.

There’s a lot of tricky questions that arise that aren’t touched on in this piece. A name change would need to be a slow and thoughtfully planned process – staffing, volunteers, timing, budgets, and not to mention the new name itself. There are likely other costs that haven’t been identified yet. We might not even like the new name, but remember, it’s not for the majority of current genetic counselors – it’s for the future of genetic counseling.

Misha Rashkin has been a genetic counselor for 10 years. He is a clinician and specializes in oncology. He has a longstanding interest in the ethical and legal issues of genetic testing, particularly the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act (GINA).

I am one of many people promoting international genetic counseling that is based on the historical, cultural and ethnic needs of the diverse individuals and communities being served. In some respects, this is a J.E.D.I. initiative on a global scale. If we in the United States change the name of genetic counseling it will have international consequences, although I have no way of knowing where, when or to what extent. We also need to keep this in mind as discussion continues.

Jon Weil

Misha – Thank you for bringing my attention to a topic I should have addressed in my original posting. Indeed increasing DEIJ is critical to the future of the profession but I disagree that changing our professional name would lead to increasing the diversity of the profession. Here’s why:

A new professional name would create a title that no one will have heard of. It would involve a large PR effort to educate the public, or at least college and high school students if you wanted to aim at recruitment. So we would be starting from Ground Zero whereas currently at least students who may have heard of genetic counselors could search the Internet and get loads of information. It also assumes that changing the name of the profession would have equal impact in increasing the number of students from all non-European ethnicities, LGBTIQA+ folks, and people with disabilities (presumably the largest but not only groups DEIJ policies target). This may or may not be true to varying degrees.

However, even when made aware of the profession, research suggests that the name of the profession is itself not a significant barrier. For example, in the study by Price et al. (https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1280), genetic counseling recruitment emails were sent to 124 chairs of biology or psychology departments of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). In addition, 90 students from a biology class at an HBCU were given either a brochure or attended a presentation by an African-American second year GC student. Following this outreach, not a single student or career counselor reached out for more information about pursuing a career in genetic counseling.

The study by Alvarado-Wing et al. (https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1419) found that while GC students from racial/ethnic minorities cited lack of awareness of the field as one of the barriers to entry, study participants suggested the solution was increasing awareness of the field in high schools and colleges that serve largely minority populations. They indicated that main barriers to entering the profession were the financial costs of applying, the hassles and costs of interviewing, and the lack of diversity in the field. For LGBTIQA+ students, O’Sullivan et al. (https://doi.org/10.1002/jgc4.1760) report that their perceived barriers were concerns about revealing their identities and how they would be treated by their programs and fellow students.

Furthermore, Gerard et al. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-018-0284-y), in a study of 1389 undergraduate students in the sciences from 23 universities across the US found no significant differences among ethnic groups in awareness of the profession, although there is some variability among other studies on this point.

Whatever differences in awareness of the profession there may or may not be in any of the cited studies, participants did not mention changing the name of the field as a means of increasing awareness or interest.

The underlying complex historical, social, and economic factors, along with explicit and implicit biases, that led to the current homogeneity of the profession are very unlikely to be overcome by changing the profession’s name. NSGC, and individual genetic counselors, would be better off focusing their efforts and resources on reducing the known barriers to entry into the field than in trying to come up with a clever name that would somehow magically increase the diversity (and not just ethnic diversity) of the profession but still capture the essence of what genetic counselors do.

I don’t object to the idea of changing the profession’s name. I just haven’t heard a persuasive enough argument to convince me that it’s worth the effort. But of course, my opinion is less important than the thoughts and opinions of the current generation of GCs.

Hi Bob,

Always great to hear your perspective. In the hopes of finding an area of agreement, I’ll point to this paragraph from my above article:

“To summarize, the benefits and costs of changing the genetic counselor title have not yet been fully flushed out. The debate at NSGC, while very thought provoking, was a starting-off point. We need to identify the best contender for an alternate name, and assess the benefits the alternate name is likely to generate…In parallel, we need to understand what the costs would be specifically for genetic counselors…Once we have a better sense of what a name change would mean specifically for genetic counselors, then we can weigh the estimated benefits of the identified new name against the estimated costs.”

Here’s an excerpt from the paper you referenced, from Price et al:

“Unfortunately, no respondents from either group expressed an interest in receiving additional information about genetic counseling. This might reflect a genuine lack of interest in the profession or that the provided method of expressing further interest (emailing the PI) did not meet the needs of this student population. Based on the fact that genetic testing has become more widespread and accessible in the past 15 years, new research to assess and understand existing misconceptions among students regarding genetic counseling should be undertaken…This study confirms that beyond the current approaches to recruitment, novel strategies will be necessary to attract more African Americans into the genetic counseling profession.”

I advocate for more research and open-mindedness, and so does one of the papers you cite. It’s also important to note that the study’s recruitment efforts in the Price et al paper were unsuccessful, and the authors weren’t able to determine the reason for the lack of success. So perhaps we can all agree that more research is needed? As I said in the above article, “If we can’t identify a new name that would propel NSGC’s J.E.D.I program, then it’s not worth the cost and effort.” And of course, you just wrote “I don’t object to the idea of changing the profession’s name. I just haven’t heard a persuasive enough argument to convince me that it’s worth the effort.” So it sounds like everyone agrees, more research is necessary?

It also seems that you haven’t attempted to debate my contention that licensure and Medicare recognition should not be used as reasons to avoid exploring a name change further. Perhaps we can also agree on that.