What is the economic worth of one person’s life? That question was raised yet again in a recent paper on expanded carrier screening (ECS) that justified an expanded carrier panel based on the cost-savings garnered by avoiding the birth of people with any of 300 mendelian disorders. A quick and likely incomplete literature search revealed other similar publications from around the globe (Azimi et al., 2016; Beauchamp et al., 2018; Busnelli et al. 2022; Clarke, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). NSGC’s Expanded Carrier Screening Guidelines also point to economic gains as one of the benefits of carrier screening. Other professional guidelines and research papers do not discuss the economic benefits of expanded carrier screening, though read carefully, the disability avoidance/cost savings theme is often an undercurrent. To me, economic justifications for ECS raise serious concerns.

The quantification of saved costs over time will help to critically examine the medical necessity of ECS as a proactive health screening strategy. – NSGC Expanded Carrier Screening Guidelines,2023

To be clear, I don’t object to carrier screening per se and a “pan-ethnic” panel can make more sense than an ethnic-focused panel. All patients deserve the right to make complicated and highly situated reproductive decisions and access to genetic testing should be fair and equitable, points which most professional guidelines agree on. My concerns arise from the purported economic benefits of ECS through disability avoidance (I, along with Katie Stoll, have some other concerns about ECS besides economic cost benefit analysis).

But first some historical context.

During medical genetics formative decades in the mid-20th century, the concept of cost-savings by preventing the birth of people with genetic conditions was baked into the field, using ingredients leftover from eugenics. Many leading geneticists at the time preached about the economic and other costs to society of genetic mutations (and by extension, the worth of people who carry such pathologic gene variants), and how it was important to eliminate these pathologic variants to save society money and to preserve the future of humanity itself. While post-World War II geneticists typically disavowed old school eugenics, many of their concerns continued to echo the field’s eugenic origins.

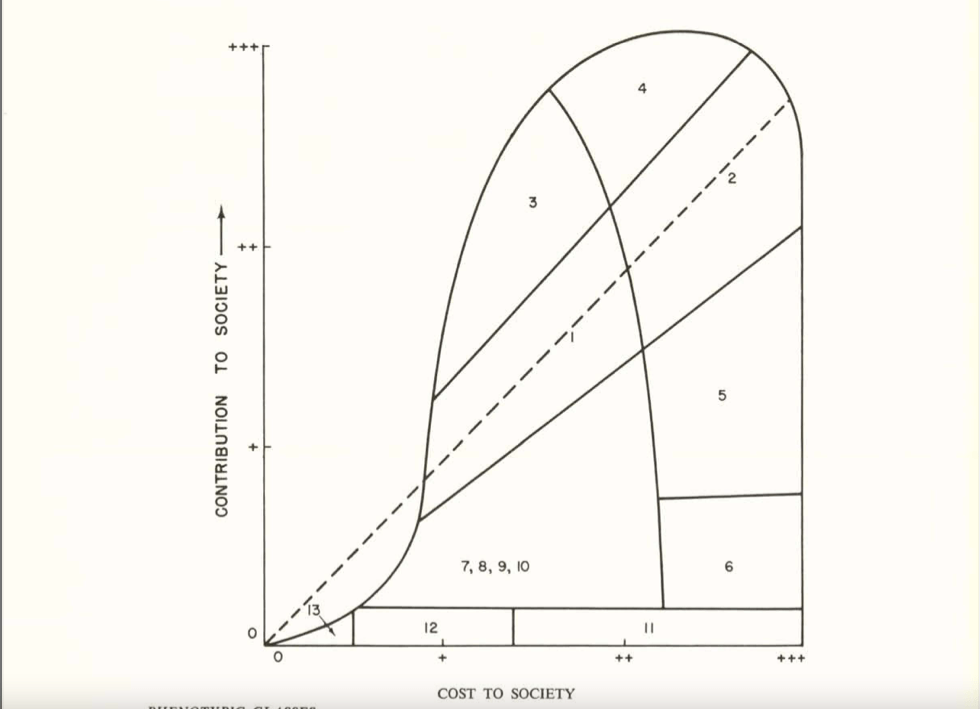

Let me illustrate this history with a notable example. In 1954, the National Academy of Sciences formed a group called The Committees on The Biological Effects of Atomic Radiation (often called The BEAR Committee), six separate committees that were charged with reviewing the available data on the range of biological effects of atomic radiation. A 1960 report from this group detailed the findings from the Committee on Genetic Effects of Atomic Radiation. The genetics committee was comprised of some of the leading brilliant geneticists of the day – George Beadle, Bentley Glass, James Crow, Theodosius Dobzhansky, Herman Muller, James Neel, and Sewall Wright, to name a few. Sewall Wright, in his chapter in the report “On the Appraisal of Genetic Effects of Radiation in Man,” divides humanity into 13 groups, based on intellectual, behavioral, and physical traits. Wright then decides the degree to which each category’s contribution to society is greater or lesser than its cost (as far as I can tell, based on Wright’s opinion and zero data). Some examples of these categories give an idea of their flavor:

1. In the first category, which includes the buIk of the population, there is an approximate balance between contribution and cost, but both at relatively modest levels.

4. In this category are those who cost society much in term of education and standard of living but who contribute much more than the average at their level of cost.

6. We may put here individuals of normal physical and mental capacity whose cost to society outweighs their contribution because of the antisocial character of their efforts: charlatans, political demagogs, criminals, etc.

8. Low mentaIity but not complete helplessness.

10. Mental breakdown after maturity, especially from one of the major psychoses.

Sewall Wright, great statistician that he was, then graphed out these categories in this figure:

People in categories above the dashed midline contributed more to society than they cost, for people in categories close to the midline their cost/benefit was a wash, and people below the midline cost more than they contributed. In Wright’s view (and presumably the view of most of the genetics committee), anybody in Categories 7 or below cost more to society than they were worth. Oddly, those in Categories 5 and 6, were “acceptable” to Wright, even though their cost to society were greater than their contributions. He may have had a soft spot for playboy types, charlatans, and criminals, although he was also unsure of the genetic contribution to these traits .

Wright’s graph did not go unnoticed. Victor McKusick, whose obituary called him “The Father of Medical Genetics,” reproduced Wright’s graph in his 1964 short book Human Genetics, one of the earliest modern medical genetics texts. On page 141 of McKusick’s text, he goes on to say “No one would dispute the desirability and scientific soundness of encouraging reproduction of intelligent persons who are an asset to society.” And it didn’t end there. Cost effectiveness studies continued to be raised to justify the introduction of heterozygote carrier screening and amniocentesis in the 1970s and beyond.

From an ethical perspective, I find it appalling that the cost-savings to society is hailed as a benefit of expanded carrier screening. Do we really measure the worth of a human life by how much money they contribute or cost to society? Isn’t that what people with disabilities, their supporters, their families, and disability scholars have been screaming at us for like a million years? Are we that tone deaf that we can’t hear their shouting? Are we just pretending to hear them or are we simply ignoring them? Isn’t a human being’s worth measured by non-economic factors? Who’s to say whose life is more worthwhile than others or how it should be measured? Why is it that people born with a genetic condition are less valued than people who develop disorders after birth that are even more economically burdensome, like dementia, lung cancer, diabetes, and heart disease (the risks for many of which can be reduced by low cost interventions like improving diet and exercise, and avoiding tobacco and excessive alcohol intake)?

Cost-savings justifications are also incompatible with Diversity, Equity, Inclusiveness, and Justice (DEIJ) initiatives. Money-saving justifications imply that if you are born with a genetic condition and cost society too much money, we are not going to include you. The message is that we support DEIJ for the “right” kind of people, those whose genomes and phenotypes aren’t too costly.

This is the same kind of bad as the rationale offered for sterilization of (mostly) women (and mostly minorities) that continued into the 21st century. Government agencies and individual physicians decided that some people were not fit to be parents and their offspring were an economic drain on society because of “what you pay welfare for these unwanted children.” The almighty dollar can bare the underlying harsh calculus of a society’s ethical norms. Ultimately, a society pays for what it wants to pay for.

From a technical standpoint, many cost-effectiveness studies suffer from some serious flaws. For example, the Beauchamp et al. paper mentioned above includes 176 conditions in their analysis. Realistically, and which the authors acknowledge, there is no way to obtain reliable lifetime costs of all 176 conditions, given the rarity and variable prognosis of most of them. Also, the greatest economic cost benefit comes from the conditions associated with increased likelihood of survival to adulthood and the attendant need for ongoing care, such as Fabry disease, cystic fibrosis, the hemoglobin disorders, and Wilson disease. Adding on dozens and dozens of other uncommon conditions, often associated with early death, does not add much to the economic savings (a point also made in the paper by Azimi et al., cited above).

Cost-savings studies also often make the erroneous assumption that people who have a genetic condition make little or no economic contributions to society. Tell that to all the hard-working adults with Fabry disease, cystic fibrosis, deafness, hemoglobinopathies, etc. Not to mention the many non-economic benefits that any individual – regardless of their genome or phenotype – may “contribute” to society, such as joy, love, friendship, community, artistic creativity, etc.

But you might argue that health resources are limited and saving billions of dollars can’t be ignored, whatever the exact amount. That saved money could go to treating people with genetic conditions. Well, first off, there is no reason to believe that such abstractly saved money would be funneled directly into the care of patients with genetic conditions, or for that matter back into the health care system itself. The theoretically saved money could just as easily wind up funding some legislator’s pet project.

Furthermore, the savings are not quite as impressive as they sound. For arguments sake, let’s accept the estimates of Beauchamp et al. that on average each condition incurs a lifetime cost of $1.1 million (US) and that 290 of every 100,000 pregnancies are affected by one or more of these 176 conditions. Assuming about 3.6 million births in the US each year, that would result in 10,440 children with one of the screened conditions. At a lifetime cost of $1.1 million each, that adds up to ~$11.5 billion in savings over their lifespan (I am making a “best” case but unrealistic assumption that all at risk couples are identified and all affected births are avoided by preimplantation genetic testing, prenatal testing and termination, avoiding reproduction, gamete donation, etc. Cost-effectiveness studies of course don’t make such unrealistic assumptions).

On the other hand, the annual (not lifetime) spending on all health care in the US is $4.3 trillion, per the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The lifetime costs of caring for people with the conditions included in an expanded carrier screening panel is barely a rounding error in annual health care spending in the US. Is the purported savings benefits of expanded carrier screening worth a rounding error, in light of its ethical shortcomings?

Figures 2a and 2b from the Beauchamp et al. reference cited above, illustrating the cost-effectiveness of different carrier screening strategies. Note how the graphs visually evoke the Sewall Wright graph above.

Another justification offered for ECS is the claim that money is saved by shortening the diagnostic odyssey and thus reducing visits to specialists and avoiding unnecessary and inappropriate treatment and testing. Certainly shortening the diagnostic odyssey is a laudable and important goal. However, cost calculations based on that claim are likely to be flawed. We don’t know how many babies born with the screened conditions would experience a diagnostic odyssey, how long the odyssey would take for each condition, and how much unnecessary spending would have been avoided. Nor do we really understand how many children undergo the diagnostic odyssey overall or what percentage of these journeys might be avoided by expanded carrier screening. Besides, the diagnostic odyssey could be more effectively shortened – though by no means eliminated – by expanding newborn screening and/or improving the availability of, and access to, whole genome sequencing, which would allow diagnosis of a much broader range of conditions than those included on carrier screening panels.

A potential and subtle danger of emphasizing the economic benefit of ECS lies in the absurd economics of healthcare that results in the high cost of new and innovative ways of treating genetic disease based on the underlying pathologic variant. Delandistrogene moxeparvovec-rokl (Elevidys), an anti-sense oligonucleotide (ASO) for approved by FDA in June for treating Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients with certain dystrophin variants, is priced at $3.2 million (US). As pointed out by Dan Meadows in this space a few weeks ago, the cost of nusinersen (Spinraza), another ASO, to treat some forms of spinal muscular atrophy, is estimated to cost ~$750,000 (US) the first year and $375,000 per year thereafter. Such high costs of treatment further bolster the belief that treating genetic disease is too costly. Paradoxically, just as at least partially successful treatments are finally becoming available for some genetic conditions, there may be a move to further prevent more births of people with certain genetic conditions in order to save money.

It’s tempting to equate cost-savings with eugenics. However, I think the eugenics label adds nothing to the discussion, other than being an accusation that turns the discussion into an argument. Whether or not it’s eugenic depends on how you define eugenics, and there is no widely agreed on definition. I think it is inaccurate to broadly label medical genetics and genetic counseling as modern day eugenics. Nonetheless, arguments for cost savings and disability prevention betrays the field’s eugenic roots and how we have not fully come to grips with our history. The graphs and table displayed in this post are not exactly the same, but they do share a pedigree. With each generation, the graphs and tables change to reflect their times, but the underlying message remains constant.

Medical geneticists and genetic counselors are not an unethical bunch. In fact, I have always been impressed with how much we struggle with complex ethical issues on a daily basis. But our vision can be subtly influenced by our history and by the fact that many – probably most – clinical and laboratory positions rely on the availability of genetic testing. We try to so hard to be good but sometimes it blinds us to the bad we might do. As Devin Shuman so elegantly reminded us in this space last week, the good intentions of our ableist assumptions can do a lot of harm. It’s about time we shed the ethical baggage of economic savings based on avoiding the birth of people with disabilities.

Your points about the complexities involved in assessing the true economic impact, including long-term considerations and ethical concerns, are well-taken. Healthcare decisions should go beyond short-term cost-effectiveness and account for broader societal benefits, especially in the realm of genetic testing, where early detection can lead to better patient outcomes and reduced healthcare costs down the line. I agree that a more holistic approach is needed, one that considers the emotional and psychological aspects for individuals and families facing carrier testing decisions. Additionally, involving genetic counselors and healthcare professionals in the decision-making process can provide valuable insights and support to those undergoing carrier testing. As the landscape of genetic testing continues to evolve, it’s crucial for policymakers, healthcare providers, and researchers to engage in ongoing dialogue about how to strike the right balance between economic analysis and the ethical and medical considerations that underpin expanded carrier testing. https://www.ourgreenstreets.org/org/asda-shipley-recycling-bank/